Despite being shy growing up, Dawn Staley was damned if she was going to let it derail her dreams of becoming an Olympian. The exceptionally reserved girl from Philadelphia never wavered in her drive to play professional women’s basketball—this at a time when there wasn’t even such a thing as the WNBA. She intercepted any bouts of shyness by keeping her eye on the endgame: representing her country at the Olympic Games. The strategy worked: Staley, 55, has four gold medals to her name: three as an athlete and one as head coach for the United States national team (among a myriad of other accolades). “I am terminally shy but I’ve had enough experiences to be ‘on,’ whenever I need to be ‘on,’” she says.

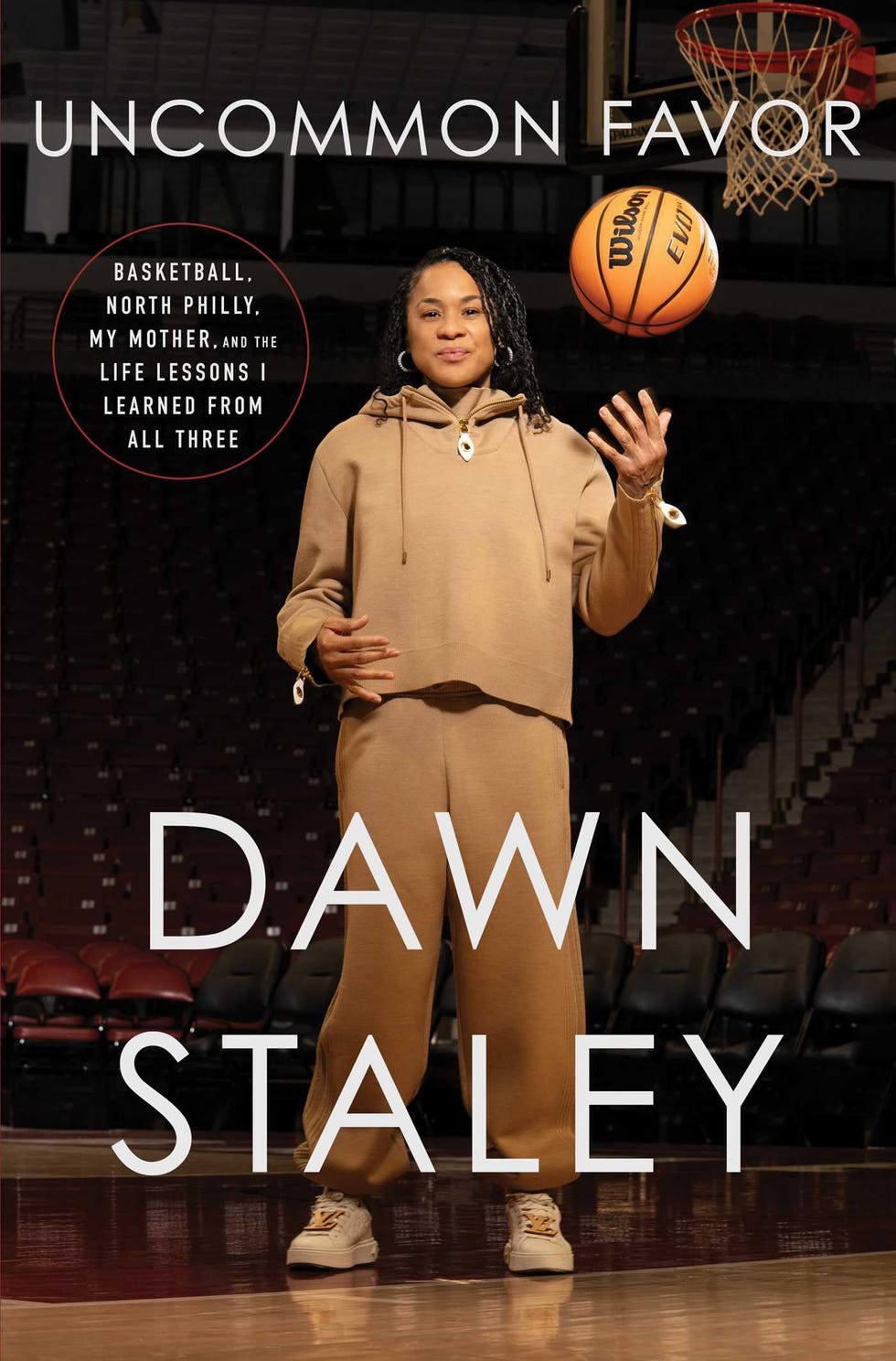

Being “on” isn’t just about playing or talking game: to Staley, it also means pushing back against anything that doesn’t align with her values as a Black woman about the game. “I don’t mind fighting,” she writes in her new memoir, Uncommon Favor: Basketball, North Philly, My Mother, and the Life Lessons I Learned From All Three, “I feel like I’m constantly fighting something. Social injustice, pay inequity, disparities in the treatment of women’s and men’s collegiate and professional athletics, intolerance. I’ve been fighting my whole life. It’s second nature to me.” She has never backed away from the fight. “Truthfully, I welcome it,” she adds. “I need opposition in my life. It sharpens me like a blade against a grindstone. It winnows my focus on the task at hand.”

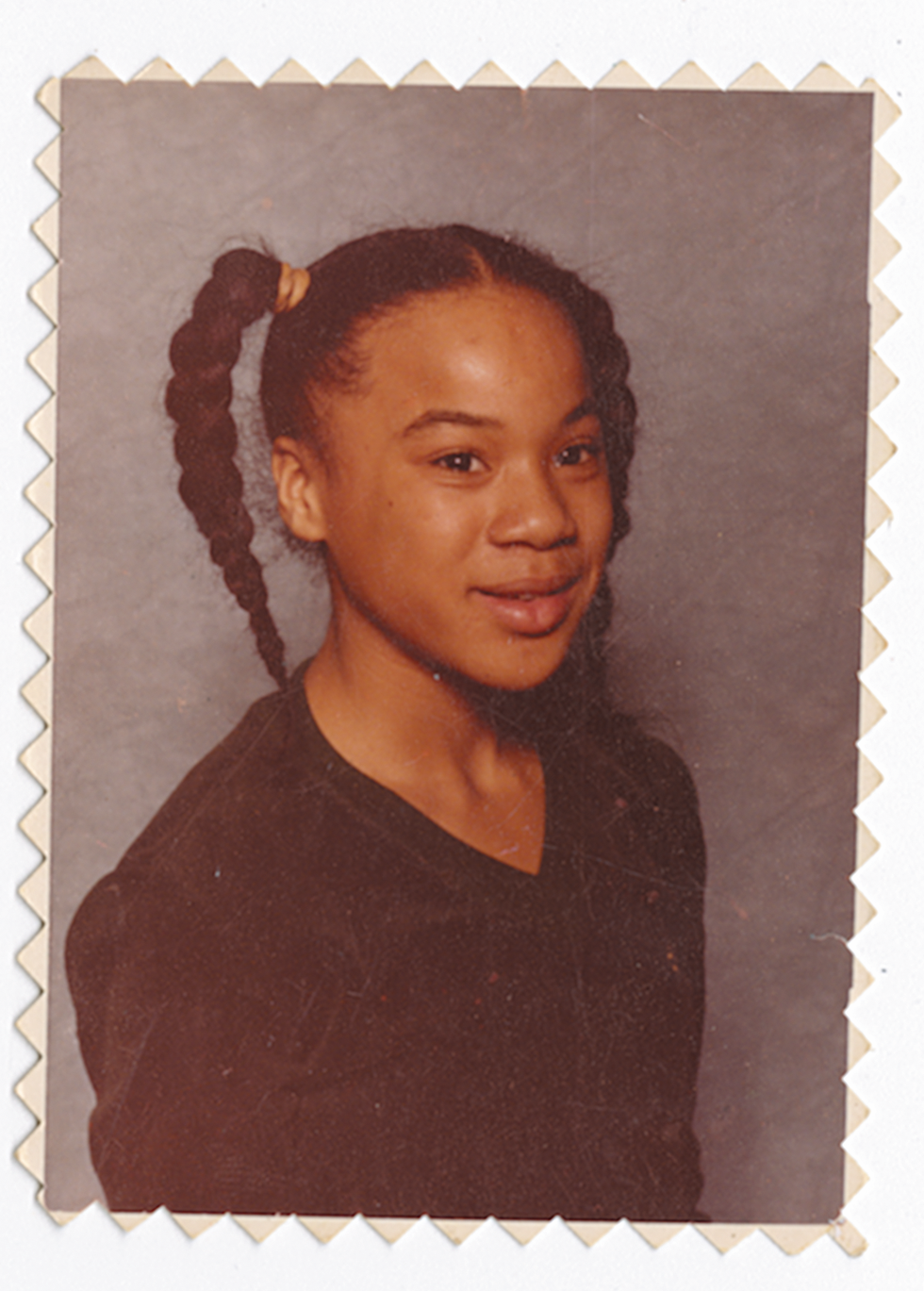

As a girl, Staley resided with her family in the Raymond Rosen housing projects of North Philly, but really, she lived mostly inside her shell. Being the youngest of five children in the row home meant there was a lot of back and forth: everything was a competition and she was always on the losing end. It could be anything from who got into the bathroom first in the mornings to who got hold of the phone in the evenings. “I may have been born competitive, but my environment definitely added fuel to that fire,” she writes. Because she ranked at the bottom of the family hierarchy, the introvert in her didn’t mind being invisible: “I was intensely withdrawn.”

Staley didn’t catch her personality from her mother. Estelle Staley was a sociable, active member of the community. “My mother loved people,” she says. “She did anything for anybody—to a fault. People would take advantage of her and she knew it. But she allowed it to happen because she made that choice. Her heart was in the right place.”

On home turf, however, nobody got past Estelle. If a child whose turn it was that week to do the dishes didn’t do them by the time she returned from her job of cleaning houses, the dishes were literally dropped to the floor one by one. That meant twice the amount of cleanup for the culprit.

The confining nature of her chaotic, crammed household compelled Staley to express herself, at least physically, elsewhere: on the local basketball court. “Basketball was me talking,” she writes in Uncommon Favor. “I was free. There was room for me to breathe…To release the person I longed to be.” As a die-hard Philadelphia 76ers fan, “The only thing I really looked at growing up was the NBA,” she tells me. “I only dreamt of things I saw.”

Observing Hank Gathers in the flesh fueled the 11-year-old Staley’s growing obsession. Gathers, the late college basketball player for the Loyola Marymount Lions in the West Coast Conference (WCC) where he was named Player of the Year, grew up in the same housing projects as Staley. “We used to go to the same rec center,” she explains. The 6-foot-7 star player would play hard but was soft on the kids who came in the way of their games, primarily Staley. “If Hank and his friends were playing on one side of the court, I would run out on the side of the basket that they weren’t playing,” she says. “But they would hurry up and come back down in a fast break situation so I would try and scoop my ball off the court before I interrupted their game.”

Gathers, who would collapse on the college court at 23 years old from a heart condition (“He took his last breath doing the very thing he loved,” Staley recalls), took notice of Staley’s own talent and would persuade the other guys to let her play with them. Joining the big boys at the rec center made Staley naively believe she could one day play with the big boys in the NBA. “When I’m growing up I’m working towards being a point-guard for the Sixers. As I got older, I realized that wasn’t in the cards, so then what was the next thing? It was something I could see other women doing and that’s where my goals of going to college and playing basketball at that level came from,” she says. “It gave me a path to follow and it helped me to stay focused away from the many distractions that the Raymond Rosen projects presented.”

Staley started to see proof that she was on the right path as early as in eighth grade: a letter of interest from Dartmouth College. In retrospect, she can see that the letter was simply an invitation to a basketball camp—one of hundreds sent to students all over the country—but at the time, Staley saw it as the first step on the ladder to her destiny.

One thing led to another. During a summer-league tournament game at Temple McGonigle Hall while she was a student at FitzSimon’s Junior High School, Staley scored 25 points with 10 assists and 10 steals. John Chaney, the men’s basketball coach was so impressed with her game that she was invited to join his weeklong co-ed basketball camps. There, she found herself in new company among peers who were determined to play. Staley did more than that: She pushed her team to go harder and be better. The meeting with Chaney would become even more momentous: Years later she would coach alongside him when she took over the Temple Owls as coach.

Because winning was all-important, she had no problem being coachable. Getting along with the girls on her team was a whole other story. As she transitioned from competing with boys to playing on all-female squads, Staley felt her female peers were disappointing. They were so much softer than her: Staley’s passes were harder and she’d roll her eyes at the girls who would wince and shake their hands from the sting of the ball when it was passed to them. She felt they weren’t as serious about the game as she was. “I’d been forged on the courts of the projects, going up against all the dudes…I had to prove myself and be exponentially better just to get an invite to the party,” she writes.

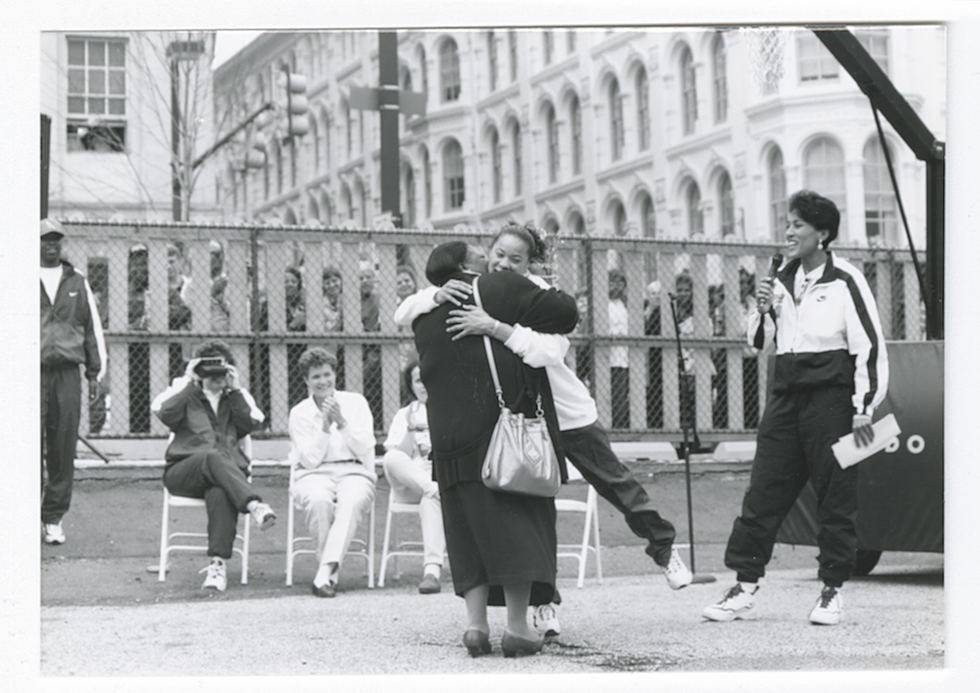

Soon enough, she started playing with girls in her own league. When she was in her early teens, Philadelphia broadcasting agent Sonny Hill invited Staley to play in his regional competitions. The girls she came up against were made of the same mettle she was—likewise legends in the making: Yolanda Laney, Linda “Hawkeye” Page, and Marilyn Stephens-Franklyn. She also joined travel teams (Estelle forced Staley’s older sister, Tracey, to drive her to all the games) which gave her a feel for all kinds of different venues and crowds, helping her to become a well-rounded player.

By the time she started high school at Murrell Dobbins Career and Technical Education High School, Staley was already considered one of the best players in the country, averaging 34 points per game. Her team didn’t lose one game her whole high school career and she won the title of national high school player of the year. During this rise, Staley was inundated with hundreds of letters from colleges as well as solicitations from recruiters. The University of Virginia and Pennsylvania State University, both of which had been courting her since eighth grade, were the top contenders on her list. She ended up going with a scholarship from UVA because she didn’t want to go to a school that had already won a national championship. “I wanted to be part of building a legacy.”

In college, her head was too much in the game. Other aspects of her life suffered as a result: she was antisocial and her grades were far from great. This put her scholarship in peril and when she was summoned to the dean’s office, where Debbie, her coach, told her to charm and connect with him so that she wouldn’t be kicked out. Staley couldn’t even make eye contact. After some pleasantries, the dean told her she would have to start conforming to the way things were done at UVA. It didn’t seem to matter that she was a once-in-generation point-guard. The North Philly in her did not take to the word conform. She was not about to “kiss the asses of these preppy white people, these elitist jerks.” In retrospect, she says that word choice is everything. Had the dean used the words “adjust” or “pivot,” Staley might have been more receptive in the moment. “But this was 1989. Coaches and deans…weren’t amending their vernacular to avoid offending kids. It was a different time. Nobody cared if you were insulted or hurt,” she writes. Debbie had to do some major damage control. Still, Staley knew she had to get it together. “I realized I had to ‘play ball’ to play ball.”

When she graduated in 1992, the opportunities for women to play ball were limited. Staley remembers a male counterpart who was the men’s 1992 college player of the year: he had signed a deal with the NBA for $80 million. Staley, on the other hand, was working in retail folding shirts, earning a couple hundred dollars a week. There was no WNBA and she had bills to pay: “I was surviving,” she says. She was already feeling disheartened: a few months prior she had gone to an Olympic training center to compete for a position on the women’s basketball team. She thought she had it, but she was cut from the list. The decision seemed political. “I couldn’t say anything but my bubble was talking huge,” she says. “They told me I was too short and that I didn’t have enough international experience. Yeah well, they put somebody on the team who was shorter than me and who had never gone overseas to play. But here’s the thing: I can say it’s political and do nothing, or I can do something about it.”

Staley couldn’t do anything about her 5-foot, 5-inch height, but she could build herself up overseas. While she waited for a position to open up, she continued at her retail job and kept herself basketball-ready, but she also worked on developing better mental strength and getting rid of residual anger. Finally five months later, a shot at a position in Segovia, Spain opened up.

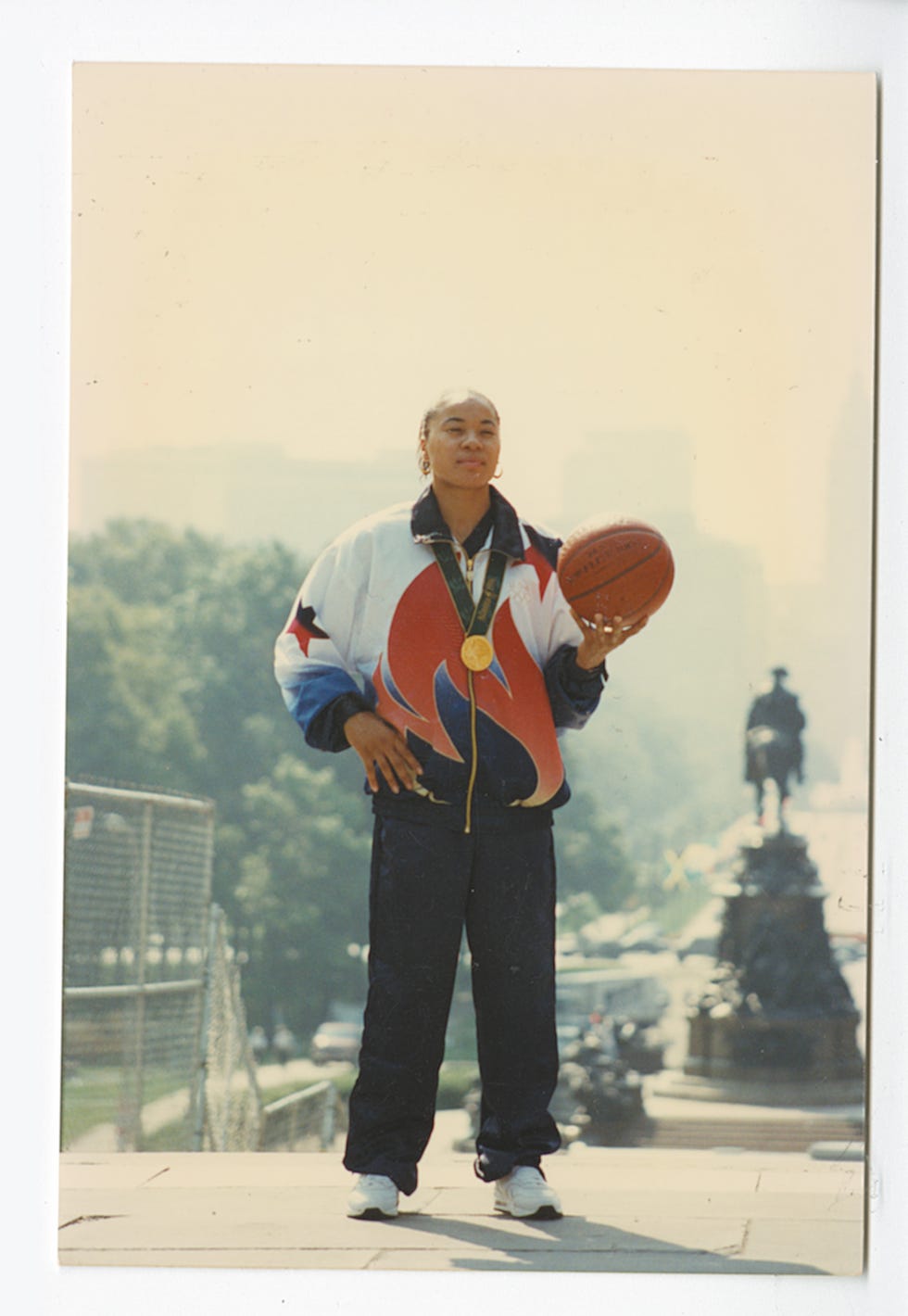

Three years of playing abroad brought just as many gold medals—one of them her first Olympic gold in the Atlanta 1996 Games. She remembers practically swaying with excitement as the Olympic medal staff went down the U.S. team line. As they were about to adorn the medal around her neck, Staley couldn’t contain herself: “Give me mine! Give me mine!” she repeated over and over. “It was so North Philly of me,” she recalls with amusement. Later, she would give that gold medal to her mother.

A couple of weeks after winning, Staley remembers feeling a depression sinking in. The world expected her to be celebrating, but she didn’t want to move her body even one iota. She had achieved her lifelong dream, so now what? The competitive edge seemed to evade her. Staley’s American Basketball League (ABL) coach was supportive and encouraged her to take some time for herself instead of getting right back to training, despite the pressure to do so. Staley has always remembered that kindness and has made it her mandate to pay it forward.

The game went on. A couple of years after the WNBA was created, Staley was selected in the 1999 draft—she would become a five-time WNBA All-Star—playing mostly for the Charlotte Sting but also for the Houston Comets. Not long after, she also became head coach at Temple University. Two more Olympic golds were added to her arsenal: Sydney 2000 and Athens 2004.

Staley retired from the WNBA in 2006 because of an insistent stirring inside her to make the full jump into coaching. “I actually played and sacrificed my body one year longer than I should have so that I could get basketball out of my system,” she says. “I didn’t want to look back. I wanted to share that space and pour that energy into my players.”

Staley has been head coach for the South Carolina Gamecocks since 2008. In 2021, she got her fourth Olympic gold, this time as head coach of the US team. Originally, coaching wasn’t in the plan for her career. “It wasn’t even a thought,” she says. “[But] I wanted to be a dream merchant for young people,” she says. “We’ve won national championships; what that represented was so much more than another player or another former athlete. It was more of a Black woman who had never been a head coach of an Olympic team: It is that representation of being the first to open doors for others to walk through.”

When her team took home the gold, Staley paid homage to Carolyn Peck—the first Black coach to win an NCAA women’s championship. “Carolyn gave me a piece of her net two years before we won as a token,” she says. “It was her way of saying: ‘You’re close, you’re close. This piece of nylon is going to be a ray of hope for you. When you’re thinking that you can’t do it, touch on this piece of nylon and know that someone who looks like you has done it.’”

This past January, Staley became the highest-paid coach in women’s basketball history when she agreed to a $25.25 million-dollar contract extension to the 2029-30 college season. “There should be more sitting where I sit,” she says. “Female coaches who have served our game for decades haven’t been paid what they’re worth. When you step out there for equal pay, it’s going to come against resistance.” Any timidity—terminal or not—has no place at the table: “We have to continue to scream at the top of our lungs to get what we deserve.”