(RNS) — Twenty years ago, Bhuwan Pyakurel was a second-class citizen in his home country. Cast out by the Bhutanese government for his ethnic and religious identity, Pyakurel and other members of the ethnic Nepali Hindu community in Bhutan, known as Lhotshampa, were forced to enter refugee camps in nearby Nepal after refusing to assimilate to the Buddhist King of Bhutan’s “One Nation, One People” policy.

“They didn’t consider me as a human,” he said, referring to officials moving him from country to country. “They put me in a truck like an animal.”

But in 2009, after 18 years of statelessness, Pyakurel and his family were given refuge in the United States. Thanks to the third-country resettlement program of the UN Refugee Agency and the International Organization of Migration, around 80,000 Bhutanese refugees like Pyakurel were offered a home and a path to naturalization in the U.S. between 2008 and 2015.

“Coming to this country and getting a citizenship was one of the best things ever I could experience in my life,” Pyakurel told RNS. “The moment I put my feet in the United States, I started thinking, here I am free in a free land, and I can do whatever I want.”

Bhuwan Pyakurel. (Photo courtesy city of Reynoldsburg)

The judge presiding over Pyakurel’s citizenship test in 2015 explained that new citizens have the responsibility to vote and run for public office. “I took that as a personal honor,” said Pyakurel, now an Ohio city council member who, in 2020, became the first-ever Bhutanese-Nepali to be elected to public office. The American dream, says Pyakurel, gave him a “second chance.”

But over the past few months, the Bhutanese refugee community has seen a number of its members deported as, under the Trump administration’s deportation program, ICE has cracked down on Bhutanese refugees who have committed crimes during the time they’ve lived in the United States. These crimes, most of them over a decade old, have ranged from theft to driving under the influence to domestic assault. Starting in the greater Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, area — a hub for the Nepali-speaking Bhutanese community — ICE has detained over 60 individuals in centers around the country.

And at least 25 have been deported back to Bhutan, the country that originally displaced them. Though their whereabouts are not all known, Bhutan has sent at least some of the deportees away again to Nepal or neighboring India. These deportees are now stateless, say advocates, and are being returned to refugee status once more.

“We were promised the rights, the freedom of this country,” said Robin Gurung, the director and founder of local nonprofit Asian Refugees United in Harrisburg, where upward of 40,000 Bhutanese refugees live. “To imagine that we will be deported back to the same country that persecuted us, it was never in our mind.”

Gurung, a refugee himself, has been working since the detainments started in March to help the community, most of whom are Hindus, to understand why this is happening. Many of the detainees, who are not fluent in English, were picked up with no warning from their workplaces or homes, some with their children first answering the door. Families have not heard from their deported loved ones, who were reportedly sent to Bhutan and then immediately sent back over the border to Nepal to join the more than 6,000 Lhotshampa (a Bhutanese term meaning “southerners”) who still live in refugee camps there.

Robin Gurung. (Photo by Hannah Yoon)

Those who broke the law should face the full extent of the U.S. justice system, Gurung says, but deporting them back to a hostile nation is troubling for the whole community, even those who became citizens, as they are unclear of what violations — perhaps even a speeding ticket — can threaten their status here. People are now carrying their legal documentation with them everywhere for run-ins with ICE.

“We are asking for accountability, transparency from the authorities,” said Gurung. “We don’t have clear evidence that they followed due process, we don’t know if the deportees were given enough time for the legal representation or were clearly informed about their deportation to Bhutan. And we don’t know if the U.S. government knows the fact that deporting these individuals to Bhutan means putting their lives at risk.”

As of now, no answers have been given from Homeland Security, the Trump administration or other federal bodies. None responded to RNS’s request for comment.

In the 1980s, the ruler of the tiny Buddhist nation of Bhutan, King Jigme Singye Wangchuck, sought to unify the kingdom under a single national identity. The “One Nation, One People” policy imposed a national dress code, a national language (Dzongkha) and Buddhist customs on the population, including the Nepali-speaking Lhotshampa in Southern Bhutan. Nepali was no longer allowed to be taught in schools, Hindu temples were converted to Buddhist-style architecture and Hindu rituals were discouraged or even banned.

After a law with stricter criteria for citizenship was passed in 1985, even the Lhotshampa who were living in Bhutan for decades were considered illegal. Protests against the king led to designating the community “traitors,” resulting in a mass ousting from the country to eastern Nepal. Middle class families were pushed into harsh refugee camps, where they huddled together in small huts, some creating makeshift temples out of bamboo.

But even after then-President George Bush implemented the resettlement program in 2008, moving to the United States presented its own challenges. Families were “pretty much starting from zero” in the new culture, language and systems. Young people became de facto translators for their parents, and mental illness among the younger generation soared. According to the National Institutes of Health, Bhutanese refugees resettled in the U.S. have had a suicide rate nearly twice the rate for the general population.

And over the course of a few years, said Khara Timsina, the founder and executive director of the Bhutanese Community Association of Pittsburgh, “there were some individuals who found that new freedom of alcoholism.” Increased criminal behavior, from DUIs to violence, became a fact of life for the vulnerable population.

The younger generation of the Bhutanese community has found stability, said Timsina, with ample aspiring engineers, health care workers and business owners, in part thanks to robust mental health programs from organizations like BCAP and Asian Refugees United. Refugees who had engaged in criminal activity in the first few years, says Timsina, had mostly already served probation or time in prison, even given work permits from the government.

“People had thought that even if they had a criminal conviction, they had finished their jail time, so the cases were closed,” he said. “They were back to normal life, working and making their family lives better. But once we started understanding that even those people were picked up, there is fear among other people who have similar situations, like pending cases or legal charges.”

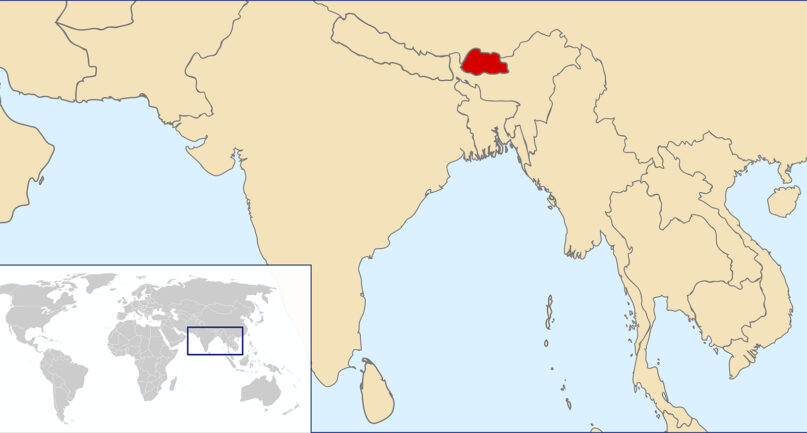

Bhutan, red, located in Asia. (Map courtesy Wikimedia/Creative Commons)

According to Pyakurel, the Bhutanese Hindus have not received support from the larger U.S. Hindu community, who are mostly of Indian origin. They have either misunderstood the refugees’ plight or been apathetic, said Pyakurel, who added that Hindu Americans have “more connection to the administration than ever in the past.” He described one Hindu politician telling him that those who did the crimes “deserved the punishment.” There is also a complication when it comes to India, some said, as the Indian government had refused to provide humanitarian aid to the refugees when they were first displaced.

Hinduism, on the other hand, has provided the community with a sense of strength and unity. A handful of Bhutanese Hindu temples and community centers in Harrisburg and Galion, Ohio — another area where Bhutanese refugees settled — have served as meeting places for conversations around politics and keep young people out of trouble. They offer Nepali language classes, alongside yoga, music and meditation.

“The temple for our generation is a kind of therapy center,” said Prem Khanal, who is the chair of the Organization for Hindu Religion and Culture in Harrisburg. “We go there, we meet our friends, we share our views and we dance and we sing hymns. And some of the older people who have been parted after leaving Nepal, sometimes they meet for the first time here in the temple after 15 or 20 years. They express their excitement in such a way that they shed tears.”

For Narad Adhikari, the founder of the Global Bhutanese Hindu Organization in Ohio, a Hindu ethos allows for a broader picture of the situation.

“We are all human beings, you know, and whether knowingly or not knowingly, some people make some mistakes,” he said. “It is our responsibility to take interest and learn from them as well. That way, our neighborhood, our nation, our society, our community, becomes stronger and more peaceful.”

Hinduism, Adhikari believes, is the greatest offering of the Bhutanese refugee community.

“Because we came as refugees, the majority of our population were not educated like the modern education here in the United States,” he said. “So what can we contribute to this country as the new citizens of America? We decided, yes, this is Hinduism.”