NASHVILLE (RNS and NPR) — The Sunday before the Tennessee Legislature voted to pass a sweeping immigration law, Republican State Sen. Brent Taylor, of Memphis, walked out of his home church before the service began.

During the pre-service announcements at Trinity Baptist Church on the last Sunday of January, Pastor Matt Crawford criticized the end of sanctuary policies for churches, which had previously discouraged Immigration and Customs Enforcement from making arrests inside places of worship.

“I hope that we can believe both in the rule of law and feel that we don’t want worship services disrupted by that. I hope that me saying that doesn’t anger you,” Crawford said. “Hopefully, we can talk about things with unity and nuance and even differences of opinion because it’s on the hearts of some of our people.”

Taylor has sponsored a slew of bills ramping up immigration enforcement, including one that would hold churches and non-profits liable if they house someone who goes on to commit a crime. He walked out of Trinity Baptist, he said, because he “didn’t show up to church that morning to hear a political speech.”

“If they’re here illegally, they are a criminal in and of themselves. And I would ask the faith leaders, do you also see it as an act of your faith to aid child pornographers or murderers or rapists?” Taylor said. “They believe that helping somebody who is here illegally that, somehow, they’re going to get some credits to get into heaven. And I just don’t see it that way.”

His walkout came less than a week into the new Trump administration, which had passed several executive orders in its first days clamping down on immigration and ramping up deportations. Taylor’s hasty exit was a portent of the looming division within evangelical churches — historically one of President Donald Trump’s most loyal demographics — over just how far to go with immigration crackdowns.

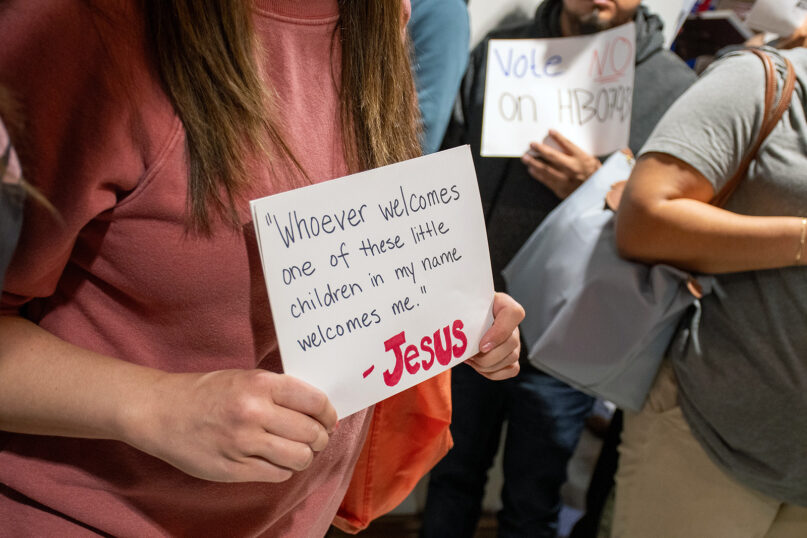

Outside a Tennessee House subcommittee, a woman holds a sign quoting Scripture in protest of immigration legislation. (Photo by Marianna Bacallao)

A 2025 poll of American evangelicals conducted by Lifeway Research, a publishing arm of the Southern Baptist Convention, reveals a complicated picture of evangelicals’ views on immigration.

Many told pollsters they see the number of immigrants as a drain on resources (44%), and the vast majority support immigration reform (80%) and stronger borders (90%). Even so, three-quarters support a path to citizenship (74%), and almost as many believe the nation has a moral responsibility to accept refugees (70%).

Evangelicals who voted for Trump were more likely to rank the Bible as the highest authority for what they believe — but were less likely to rank the Bible as the biggest influence on their view of immigration, according to the survey.

Taylor and his colleagues in the Republican Party have echoed that sentiment.

“I don’t view this necessarily as a biblical issue. This is a law-and-order issue,” he said.

However, Taylor said he does see biblical parallels to his approach.

“Heaven has an immigration policy, and hell does not,” Taylor said. “There’s a certain way you get to heaven. You can’t climb the wall. You can’t dig a hole and come in under the wall. You can’t present fake documents to Saint Peter at the gate … It’s a very strict immigration policy. Hell, on the other hand, you get there any number of ways, and you don’t have to have documentation to get in there.”

Like Taylor, most evangelicals support the deportation of convicted violent criminals, according to Lifeway, but very few — less than one-fifth of evangelicals — support deportation of immigrants who have spouses or children who are U.S. citizens.

“The vast majority of evangelical Christians, they support border security, but they also support pathway to citizenship. They support treating immigrants with dignity and respect,” said Galen Carey from the National Association of Evangelicals.

The NAE, along with two other evangelical organizations and the U.S. Catholic Conference of Bishops, in March published a report claiming that around 1-in-12 Christians in the U.S. are vulnerable to deportation or live with someone who is.

“We’re sounding the alarm that all American Christians need to be aware of what’s being proposed,” Matthew Soerens of World Relief, one of the authors of the report, said at the time.

Nuanced polling or not, institutional pushback against Trump’s immigration policies has not always landed well among its evangelical constituents, many of whom are still fiercely loyal to Trump (72%, as of an April poll by the Pew Research Center).

The Southern Baptist Convention experienced backlash for sending a letter to Trump, criticizing the end of sanctuary policies for churches.

Earlier this year, the Presbyterian Church in America gave advice to church members without citizenship on how to interact with ICE — something the PCA later retracted and apologized for following outcry from some of its congregations.

President Donald Trump waves to the media as he leaves the U.S. Capitol on March 12, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana)

But in Nashville, a blue city at the heart of a red state, one PCA church hopes to find a way through the polarization. Part of the conservative Reformed denomination but located in the artsy neighborhood of East Nashville, City Church knows its pews are divided on political issues, including immigration.

“Something that’s so very important is just having a place to be able to come together and talk,” said David Gaston. An elder at the East Nashville church, Gaston hosts a weekly Bible study and dinner for congregants.

On a recent Sunday night, a group from the church sat around a fire in Gaston’s backyard, eating dinner off paper plates.

“Meals like this, people gathering from all different sides of life, all different parts of the political spectrums, and just talking together in some ways is a little bit of an act of resistance in our current climate,” Gaston said.

That kind of resistance is why Jeremiah Sunshine drives in from the next county over to attend City Church. Sunshine, an arborist for 25 years, employs a number of immigrant workers in his tree service.

“We need people to come into the country,” Sunshine said. “Not only are they a wonderful blessing, you know, socially and culturally, but they strengthen the workforce, you know, they do all kinds of wonderful things.”

But Sunshine said he also believes in law and order and supports President Trump’s approach to immigration enforcement. He pointed to the Old Testament Book of Nehemiah, which stresses the importance of walls to protect Jerusalem.

“Any country … needs a border, an actual border that functions as a border,” Sunshine said. “If you don’t have a border, you don’t really have a country.”

Other members of Sunshine’s church — like Alice and Matthew Smith — have a different outlook.

“There are specific Old Testament passages about loving the foreigner and the widow and the orphan among you,” Alice Smith said. “Leaving the grains of your field unharvested on the edges, so that foreigners and people who are traveling, sojourners and the strangers can have food when they are in poverty.”

“It even says that if someone falls into poverty among the people of God, treat them as you would the foreigner,” Matthew Smith added. “That means care for them. That means help provide for them.”

Matthew said the Bible doesn’t specifically outline an immigration policy, so Christians can disagree about what reform should look like.

“Hopefully we can disagree kindly, even though I feel like America as a whole has lost the ability to have conversations in a civil manner,” he said.

Those kinds of conversations are part of the reason Sunshine’s family makes the drive every Sunday. He said churches closer to home were too afraid to talk about these issues.

“It concerns me how little discussion there is about it, like, it grieves me how little discussion there is about it,” Sunshine said.

But around a bonfire, the Smiths and the Sunshines can have these conversations, even if they — like the rest of the church — never reach a true consensus.

This story was produced through a collaboration between NPR and RNS. Listen to the radio version of the story.