Style Points is a column about how fashion intersects with the wider world.

Fresh out of college, still in that strange limbo between undergraduate and young adult, Elizabeth Evitts Dickinson walked into the Maryland Historical Society. It was 1998, and she was wearing “a supremely uncomfortable suit,” she remembers. “It was so bad. I was still trying to figure out how to dress like a professional woman.”

What Dickinson saw on that visit would shift her worldview. The crisp, airy garments on display were the antithesis of her stiff young-professional cosplay, which lacked pockets, leaving her juggling her lipstick and keys. She had never heard the designer’s name before, but their label read “Claire McCardell.”

“I didn’t realize that much of what hung in my closet and was folded in my drawers was, in large part, thanks to her and the work she did in the 1930s and ’40s to advance American sportswear,” Dickinson says. Not only did the pieces look startlingly contemporary, but “I recognized instantly that they provided something I wasn’t getting as a woman.” Namely: comfort, flexibility, and most crucially, freedom.

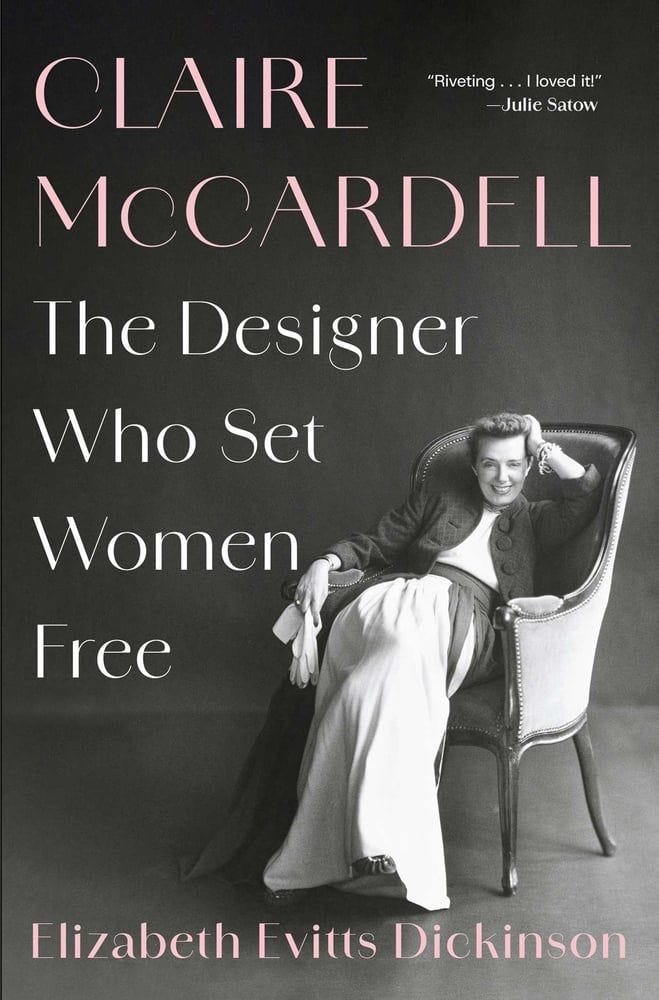

“I became instantly curious how a young woman from a rural town in Maryland became one of the most important fashion designers,” Dickinson says, “at a moment when women couldn’t even open their own bank accounts.” That epiphany led to the writer penning an article for The Washington Post Magazine on the anniversary of the designer’s famed Monastic dress. And then, to her new book, Claire McCardell: The Designer Who Set Women Free.

McCardell grew up a tree-climbing tomboy, and she always chafed at the restrictive clothes girls were expected to wear. As she once said, “Men are free from the clothes problem—why should I not follow their example?” Working her way up the design-world ladder, she focused on building in the comfort and ease women had long been denied in their clothing. Some of her innovations: a focus on mix-and-match separates before those were commonly sold. The idea of a capsule wardrobe, or what she called “the duffel-bag wardrobe.” Wrap dresses. Sweaters with attached hoodies. Athleisure like leggings and modern one-piece bathing suits. Side zippers for added convenience. And, of course, pockets.

Even though she was instrumental in creating so many building blocks of the modern fashion ecosystem, their very familiarity has made it easier to erase her achievements. “Much of what she designed has become the groundwater,” Dickinson says. “It’s so subsumed into our wardrobes already that it’s not like there’s a singular dress where we can say ‘It’s a McCardell.’”

And while her name may not call to mind a signature silhouette or an iconic handbag shape, her approach was still nothing short of revolutionary. “McCardell was one of those rare designers who was thinking about the female experience of clothes. She wasn’t as interested in the societal gaze, or the male gaze,” Dickinson says, noting that, at that time, fashion was still dictated by the whims of Parisian designers. “It would filter down as cheap knockoffs to American women who were being told to dress like the Duchess of Windsor.” Now, here was McCardell with an unpretentious alternative, which would come to be known as American sportswear.

McCardell also came along at a time when female designers, notably underrepresented at the helm of major fashion houses today, held significant power in the industry. “There really was this forgotten feminism that existed,” Dickinson notes. “[Women] basically invented New York fashion. While men mostly owned the manufacturing companies, it was women who were primarily the head designers.”

That would soon change, however. As Dickinson was writing, today’s tradwife movement was never far from her thoughts. And post-World War II, fashion and culture underwent a similar conservative shift, with women moving back out of the workforce (and the atelier) and into restrictive, wasp-waisted, bullet-bra’ed styles. McCardell was outspoken about this regressive return, says Dickinson, seeing it as “the canary in the coal mine for a larger societal death of women’s autonomy, this idea that they were seeing in fashion what women were told to be, which was beautiful, lovely, objectified, stay-at-home mothers.” McCardell publicly feuded with French designers, including Jacques Fath, “because this was a moment where men were saying, ‘Women shouldn’t be designers. Women should wear the clothes, and men are the artists.’ You start to see not just this reversion of what women were told they were allowed to wear, but also, ‘Women shouldn’t be in the workplace; women should get out of the design studio and leave it to the men.’”

McCardell died young, and her designs may not be as well-remembered as those of her showier peers. But even if this is your first time reading her name, her influence has undoubtedly crept into your wardrobe. Designers from Calvin Klein to Anna Sui have cited her as an inspiration, and versions of the garments she pioneered are still in our closets today. Every Substacker currently recommending you invest in a capsule wardrobe owes a debt to her Six Separates, the precursor to Donna Karan’s Seven Easy Pieces. And her recently reissued 1956 book, What Shall I Wear?, is the OG TikTok fashion guru. Just like Dickinson, once you’ve seen McCardell somewhere, you’ll soon start seeing her everywhere.