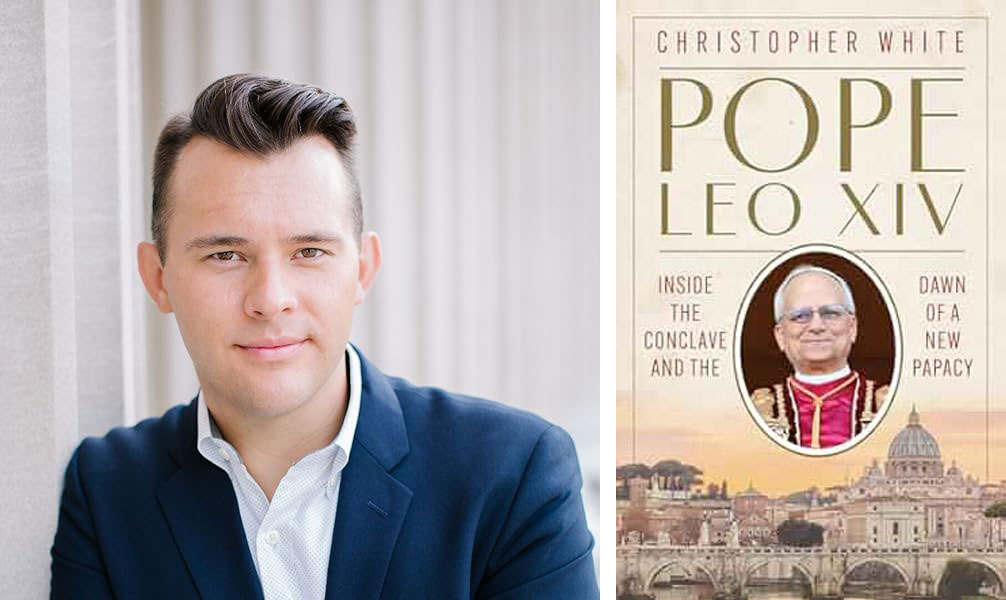

(RNS) — The cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church astonished the world when they suddenly elected a new pope on May 8 in just four ballots and little more than 24 hours. Christopher White can claim a similar achievement with “Pope Leo XIV: Inside the Conclave and the Dawn of a New Papacy.” In scarcely six weeks he has written a marvelous account of the dizzying weeks that followed Pope Francis’ death the day after Easter.

The book, filled with helpful historical background and sharply concise explanations of the inner workings of the church, is a wonder. White, until recently the Vatican correspondent for the National Catholic Reporter, has long had access to key figures that enliven his account. But in very little time he turned his familiarity into more than an insider account — it is a compelling book that gives us the big picture that the limits of day-to-day reporting make more difficult to capture.

Those of us who will miss White’s updates at NCR — he is now a senior fellow and associate director at Georgetown University’s Initiative on Catholic Social Thought and Public Life — can have hope that this is the first of many books that will find him giving texture and context to the unfolding new era in the Catholic Church.

The book is divided into three sections — first deftly summarizing the 13 years of the pontificate of Pope Francis, then recounting the conclave and finally focusing on Leo himself. A book whose title promises a focus on “Pope Leo XIV” that spends its first third on Francis might be considered a bit of a cheat. White sketches the Francis papacy with precision and a feeling of accumulating momentum. We read how Francis changed the church so much that the conclave to find his successor was inevitably a different kind of gathering, responding to a different church, than the one that elected him.

In the wake of Leo’s election, however, it’s easy to forget how precarious the fate of Francis’ reforms looked in the days leading up to the election. White traces the battle lines of what seemed to be shaping up to be a very close contest about the future of the church, dividing the major players into three camps: those who wanted to press Francis’ full agenda forward, those who wanted to continue in Francis’ direction but abandon his inclusive all-church dialogue known as “synodality” and those who sought a full repudiation.

The prelates were not the only ones doing battle. In the days leading up to the conclave, White writes, “a relatively small but extremely wealthy and influential set of Americans” threw their support behind the cardinals who wanted to scuttle Francis’ legacy.

Instead, the cardinals quickly and emphatically landed on Cardinal Robert Prevost — reports tell us the votes in favor far exceeded the required two-thirds of the 133 possible votes.

With all this background, White settles into the book the reader may have expected: a well-reported history of Prevost’s upbringing and career and a journalist’s insights about how the conclave actually went down. The author recalls in a lengthy passage his own meeting with Prevost in the cardinal’s Vatican office, where we meet the Prevost we have come to know from interviews conducted with friends and family members since he became pope: quiet, reserved, a good listener who can also be funny. Perhaps most revealingly, White offers a vivid depiction of the quality that seems to have drawn both Francis’ affection and the cardinals’ votes: Prevost is a missionary and a pastor, not a bureaucrat or a professor.

These three sections hang together quite well in a narrative that never seems to slow down. Even the digressions into history and theology are precisely targeted, giving a reader who may not know much about Catholicism just as much as they need to know to have a sense of the stakes. White even manages to conjure a little suspense despite the world knowing the outcome.

But the real delights of this book are the countless reportorial touches that place us in White’s confidence as well as in the confidence of his well-placed sources. Besides Prevost’s Vatican offices and others’, we get glimpses of Francis’ apartment in the Domus Sanctae Marthae, the Vatican guest house and even the conclave itself. We get to know the personalities as much as the politics of the church. We learn much about Leo and Francis — and Christopher White, as he divulges how he fixed on Prevost as a serious papal contender even as others smugly dismissed his chances.

The reader also comes to see the depth of White’s affection for Francis. The reporter had the chance to observe the late pope closely in small moments that affirm what many of us saw and loved in him in the bigger ones, as when Francis passes out candy to small children. After Francis’ appearance in St. Peter’s Square on Easter, the day before he died, White recalls thinking, “This was a very sick man, and he was giving it all he had.” These moments paint a picture in pointillist details that together expose a much larger landscape.

But if a reporter narrating his own more personal experience of events he witnessed is not traditional reporting, exactly, it makes this a more impressive book. It adds a dimension of humanity that makes for a more revealing and fascinating read, because it invites the reader into the story. As we read about how Leo became pope, we root for Francis’ legacy to survive the papal election.

It’s an astonishing achievement. Many more books about Leo will follow, but many authors who take more time will struggle to do so well.

(Steven P. Millies is professor of public theology and director of the Bernardin Center at Catholic Theological Union. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)