NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

President Donald Trump recently canceled public-employee union contracts for thousands of federal workers. The employees worked in agencies tied to national security, allowing Trump to invoke a national security exemption to the normal rules governing federal employees. Trump’s decision builds on his March executive order expanding the agencies covered by the exemption.

It is the latest step in a series of battles over public-sector unionism at the federal level that goes back more than a century — a debate that touches on key aspects of democratic governance.

In 1902, President Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt issued an order barring federal workers and postal employees from lobbying Congress. His successor, William Howard Taft, took a similar action in 1909 with Executive Order 1142, which focused on preventing lobbying by members of the military. Congress overturned these orders in 1912 with the Lloyd-La Follette Act, but the move did not lead to widespread public-sector unionism.

President Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919), who succeeded William McKinley after his assassination. Roosevelt was a popular leader and the first American to receive the Nobel Peace Prize, which was awarded for his mediation in the Russo-Japanese war. (Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

In 1919, Massachusetts Gov. Calvin Coolidge put himself on the political map when he fired striking Boston police officers. When he made this decision, Coolidge famously declared: “There is no right to strike against the public safety, anywhere, anytime.” Coolidge’s action was an important factor in Warren Harding choosing Coolidge as his vice presidential nominee in 1920.

FEDERAL JUDGE RULES AGAINST TRUMP ADMIN IN LAWSUIT AGAINST GOVERNMENT LABOR UNIONS

The Harding-Coolidge ticket defeated Ohio Gov. James Cox and New York’s Franklin Roosevelt. Coolidge became president when Harding died in 1923. Roosevelt eventually made it to the White House in 1932. But as president, Roosevelt recognized the dangers of public-sector unionism and opposed it. The 1935 Wagner Act, which boosted the power of private-sector unions, specifically exempted public-sector unions from its protections, stating that federal, state and local governments were not to be considered “employers” with the same obligations Wagner imposed on the private sector.

In 1937, Roosevelt wrote a pivotal letter to the president of the Federation of Federal Employees. According to Roosevelt: “All government employees should realize that the process of collective bargaining, as usually understood, cannot be transplanted into the public service.”

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt delivers one of his Fireside Chat radio broadcasts in this 1930s photo. (Stock Montage/Getty Images)

Roosevelt’s reasoning was crystal clear and has been frequently cited by conservatives — and conveniently ignored by liberals. He warned: “The very nature and purposes of government make it impossible for administrative officials to represent fully or to bind the employer in mutual discussions with government employee organizations.”

TRUMP’S CONTROVERSIAL PLAN TO FIRE FEDERAL WORKERS FINDS FAVOR WITH SUPREME COURT

In 1939, the Hatch Act included language limiting political activity by public-sector workers. The act, passed by a Democratic Congress under a Democratic president, stemmed from concerns about political activity by employees at Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration during the 1936 election. Roosevelt aide Harry Hopkins, director of the WPA, had been accused of promising jobs for votes, leading to congressional outcry and the passage of the law.

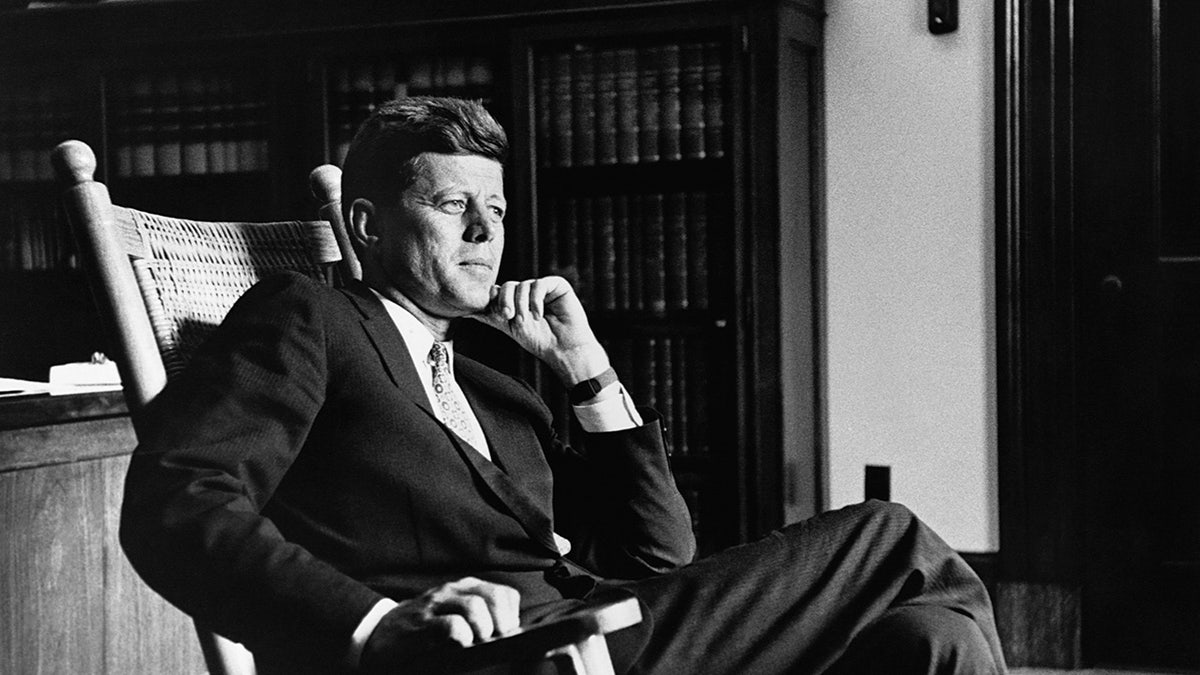

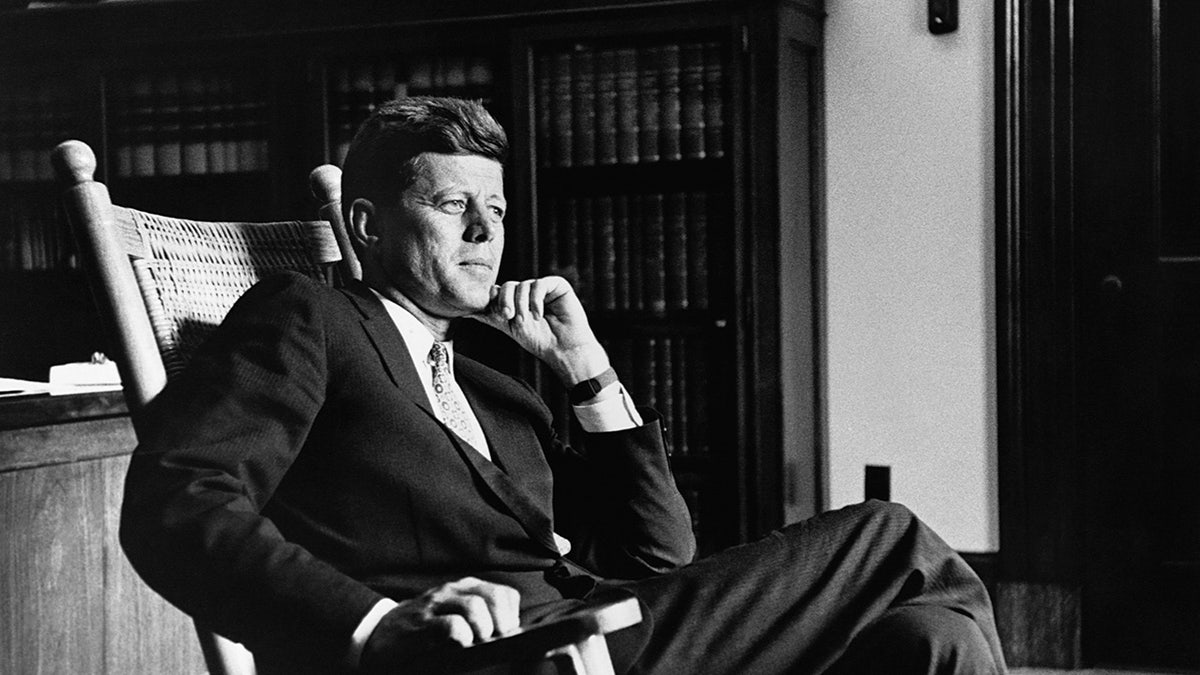

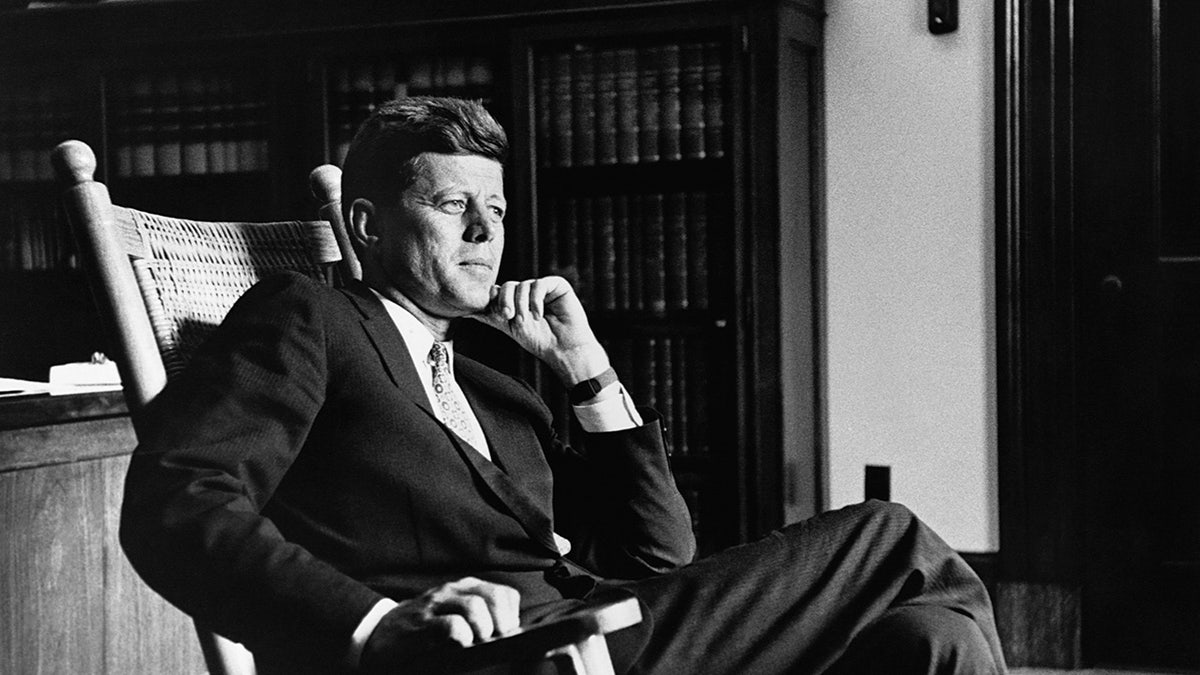

A big change towards the acceptance of public-sector unions came during the John F. Kennedy administration. In 1962, Kennedy issued Executive Order 10988, explicitly allowing federal employees to form unions and bargain collectively. But as Ira Stoll points out in his book “JFK, Conservative,” Kennedy also recognized important limitations. His order did not include the words “collective bargaining.”

President John F. Kennedy (1917-1963), the thirty-fifth president of the United States, relaxes in his trademark rocking chair in the Oval Office. (Getty Images)

He understood, like FDR, the inherent conflict of interest in granting those rights to government employees. In addition, the order said the government should not recognize any union “which asserts the right to strike against the government of the United States or any agency thereof … or which advocates the overthrow of the constitutional form of the government in the United States.”

This language showed disapproval of strikes by public-sector unions and concerns about communist influence. Kennedy also exempted the FBI and CIA from public-sector unionism because of national security concerns — a precursor to Trump’s recent actions.

If there was one president who did the most to promote public-sector unionism in the federal government, it was Jimmy Carter. Public-sector unionism had already been rising at the local level when Carter was elected in 1976. Recognizing this trend, Victor Gotbaum, head of New York’s American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), bragged in 1975, “We have the power, in a sense, to elect our own boss.”

President Jimmy Carter addressing a town meeting.

When Carter signed the 1978 Civil Service Reform Act, he expanded union power at the federal level. The law granted most federal employees the right to join unions and bargain over the “conditions of [their] employment.” Even though it included a national security exemption, the CSRA was a major step toward the current era in which, according to Philip Howard’s 2023 book Not Accountable, “the abuse of power by public employee unions is the main story of public failure in America — worse even, I believe, than polarization or red tape.”

Carter also created the Department of Education, long sought by teachers’ unions. They have been paying back Democrats ever since. A new report shows the top two teachers’ unions have given almost $50 million to left-wing groups since 2022.

CLICK HERE FOR MORE FOX NEWS OPINION

Carter’s successor, Ronald Reagan, pushed back in August 1981 when he fired 11,345 illegally striking air traffic controllers. Reagan issued a statement he wrote himself: “We cannot compare labor-management relations in the private sector with government. Government cannot close down the assembly line. It has to provide without interruption the protective services which are government’s reason for being. … Those who fail to report for duty … are in violation of the law, and if they do not report for work within 48 hours, they have forfeited their jobs and will be terminated.”

Reagan’s move had far-reaching implications. It showed the Soviets he was a man of his word, helped him maneuver more effectively on the world stage and boosted his political standing at home. Most importantly, it demonstrated that the federal government could limit the right of federal employees to strike. There had been two dozen strikes by federal workers in the two decades before Reagan’s action. There have been none since.

President Ronald Reagan walking and giving a thumbs-up gesture on the South Lawn of the White House after returning from Massachuetts. (Cynthia Johnson/Getty Images)

Since then, political organizing — not striking — has been the main battleground for public-sector unions. They overwhelmingly support Democratic candidates, using dues to fund campaigns.

In 1988, the Supreme Court in Communications Workers v. Beck required unions to give workers the ability to opt out of the portion of mandatory dues spent on politics. In April 1992, in the midst of a tough re-election campaign, President George H.W. Bush issued an executive order implementing Beck by requiring federal contractors to notify employees of their Beck rights. Bush said: “Full implementation … will guarantee that no American will have his job or livelihood threatened for refusing to contribute to political activities against his will.”

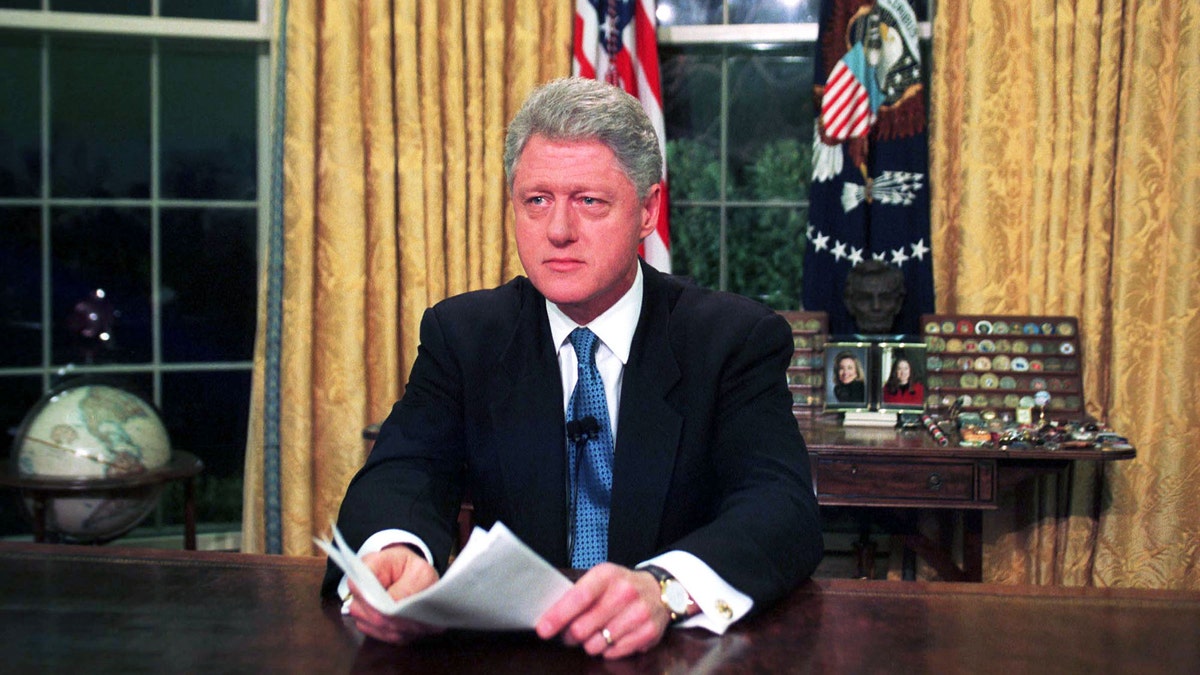

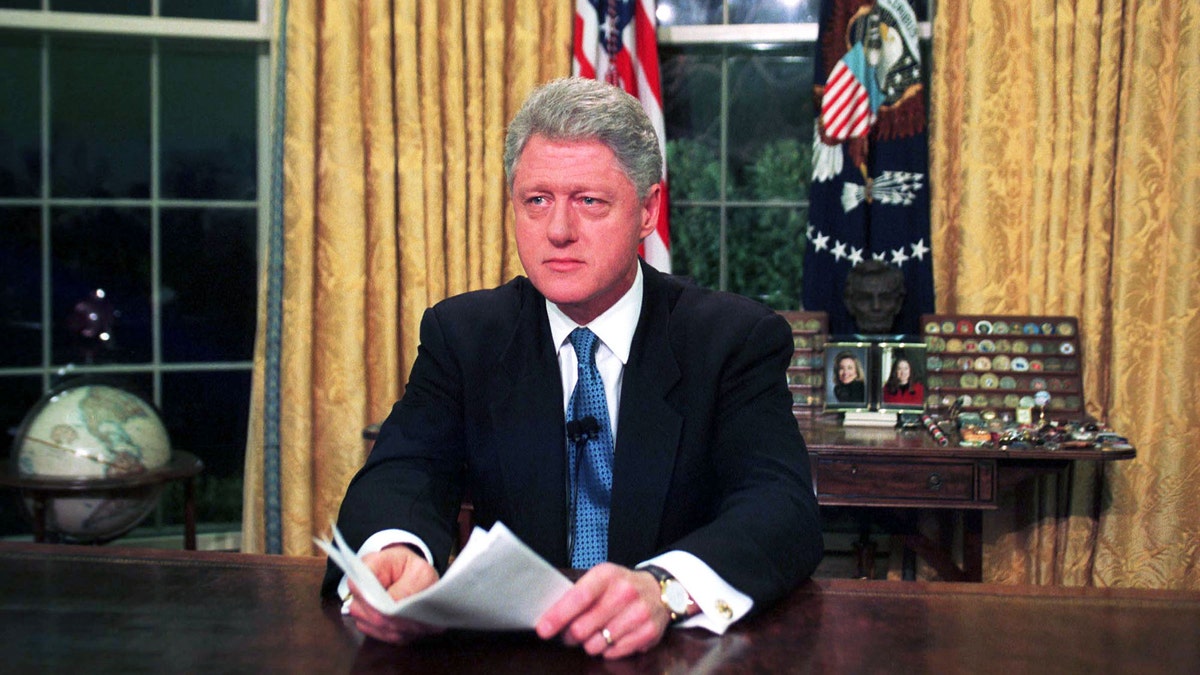

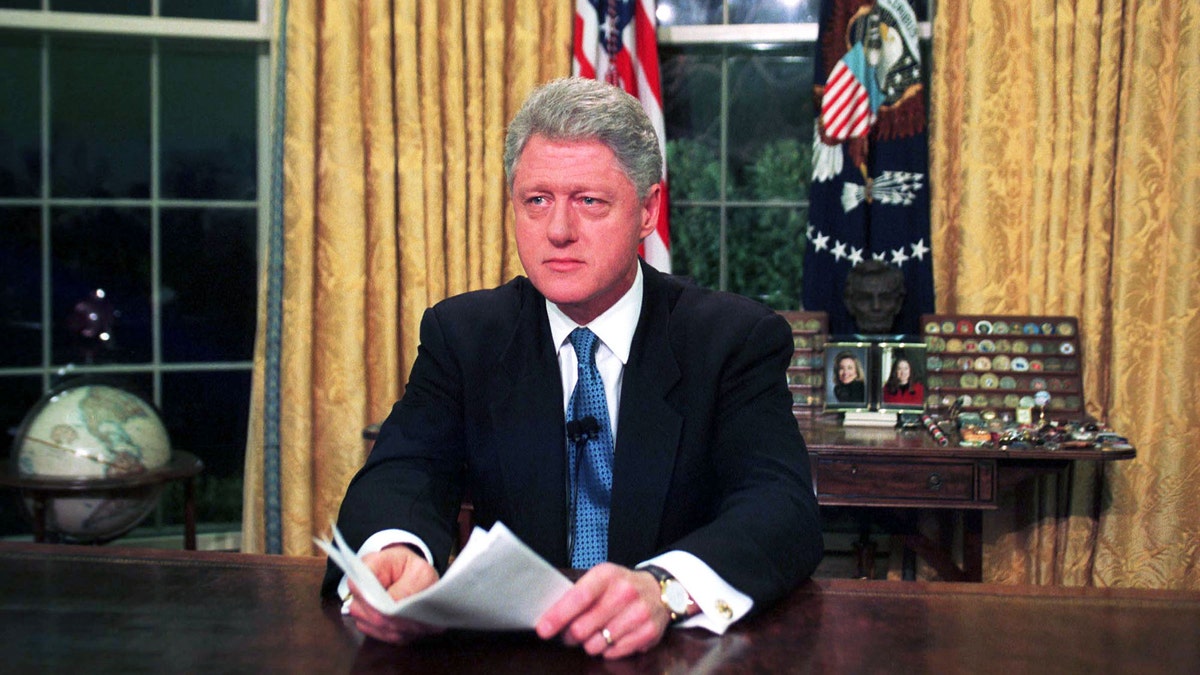

Bill Clinton, Bush’s Democratic opponent, denounced the order on the campaign trail. According to a Bush White House estimate, if every eligible worker requested a refund, union funds for campaign activities would be reduced by $2.4 billion — nearly all of it aiding Democrats. As president, Clinton revoked the order. When George W. Bush took office, he reinstated it, showing how partisan the issue had become.

President Bill Clinton in the Oval Office. ( Pool/Getty Images)

Another key fight has been over the scope of public-sector union coverage. During creation of the Department of Homeland Security after the 9/11 attacks, George W. Bush sought to exempt DHS employees from union requirements. He won legislatively, but court decisions later limited many of those exemptions. Trump’s recent actions echo that battle as he seeks to extend exemptions to agencies including the Department of Veterans Affairs. Courts will decide whether his moves fall within the law.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Looking back, presidents as different as Theodore Roosevelt, Coolidge, Franklin Roosevelt, Kennedy, Reagan, George H.W. Bush and Trump all agreed on one thing: limiting the scope of public-sector unions, especially in national security. Unfortunately, today the issue is highly partisan, with Democrats staunchly in favor of public-sector unions and Republicans looking to curtail their power.

On this Labor Day, we should celebrate American workers while recognizing the difference between hardworking citizens and public-sector unions that use their power to elect their own bosses.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM TEVI TROY