(RNS) — For many Christian kids, church camp — with nightly s’mores, goofy skits and Jesus-y singalongs — is an oasis that welcomes them each summer. For decades, that was the case for Cara Meredith, who grew up evangelical and spent 25 years as a camper, seasonal staff worker and staff speaker.

But looking back years later, the lighthearted memories sit alongside upsetting ones. She remembers being 10 years old at an evangelical church camp in Oregon, when her counselor and cabinmates mistook her shivering outside due to the cold for having some kind of religious experience.

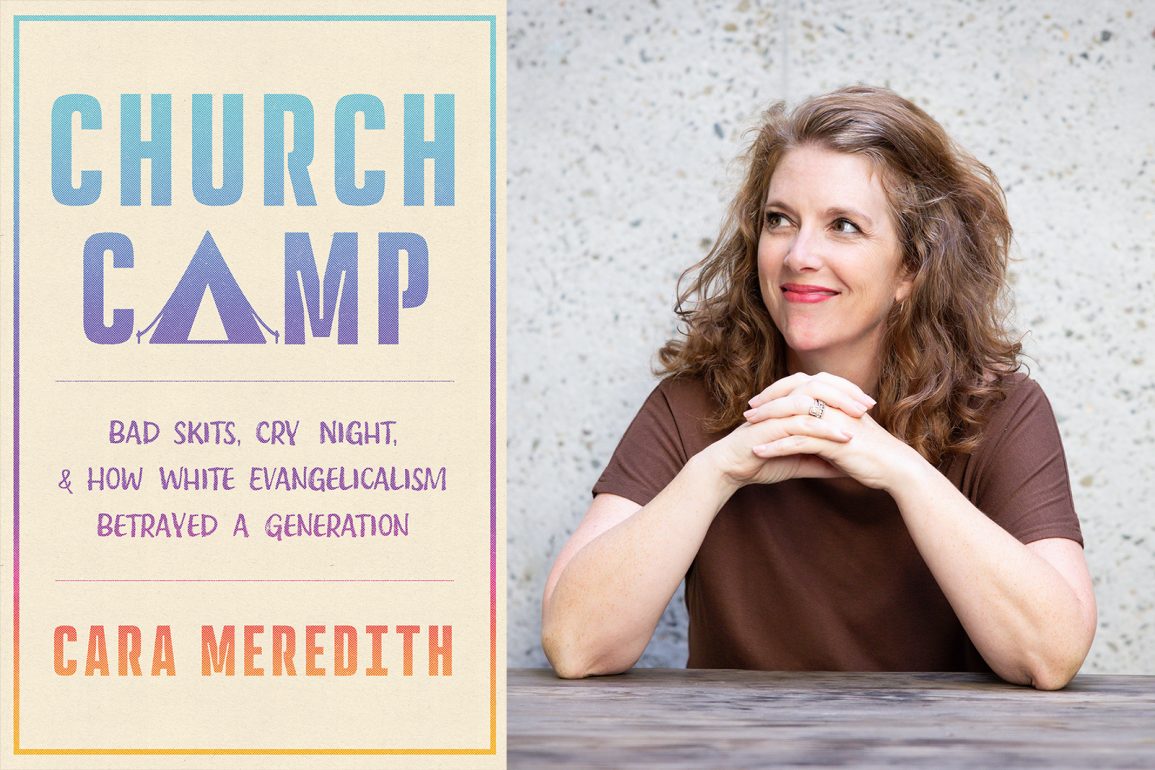

“I ended up playing into that, hyping up my own emotions and what I thought they wanted me to do,” Meredith told RNS. After all, “if you didn’t have a specific story of salvific impact on the pinnacle night of the week, then it was easy to believe you weren’t doing what you were supposed to be doing,” she writes in her new book, “Church Camp: Bad Skits, Cry Night, & How White Evangelicalism Betrayed a Generation.”

Released by Broadleaf Books in April, the book blends research, her personal account and interviews from nearly 50 people. RNS spoke with Meredith, who now resides in the San Francisco Bay Area, about camp “cry night,” rules and her hopes for church camps going forward. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What makes church camps different from other summer camps?

I’m writing about white evangelical church camps, and all of them share a focus on conversion. It’s a very different ethos than, for instance, you’d find in a mainline church camp. Because conversion is the end goal, there are a lot of similarities that happen along the way, oftentimes in a progression of messages that are preached to try to get campers from a point of disbelief to belief, or from a point of being a “lukewarm Christian” to being on fire for Jesus.

You suggest that these camps are a microcosm of white evangelicalism. How so?

I’ve had so many readers reach out and say, I never actually attended church camp, but this exact same thing happened at VBS. This exact same thing happened at youth group. This is exactly what my pastor preached from the front of the room. Sometimes they’re talking about the messages that rely on the penal substitutionary atonement theory, which centers on human depravity and on the debt that God needed to pay through Jesus.

There’s also a commonality of exclusion. For me, that was a big part of where this started. I began to see this exclusion happening to women, people of color, the LGBTQ+ community. As a woman, I realized how I was both complicit in that, but I was also on the receiving end of the exclusion. If you can understand church camps, then you’re also going to understand more about our culture today. We can look at who’s holding the power in our government, and who is influencing the government. There is power being given to particular people who hold certain values, which includes values that can be exclusionary toward people.

You write that belonging at church camp was often dependent on whether a camper played by the rules. What are some of those rules?

There’s both explicit and implicit rules. You have at camp this idea that there’s no “making purple.” Boys are blue and girls are pink, and they shall not make purple. Although, of course, everybody makes purple. So many people go to camp because they want to get a camp boyfriend or girlfriend. There are explicit rules around not having electronics, or that while you are here, you are going to have the best week of your life.

But there are also the implicit rules, especially when it comes to belonging. You belong if you say the right things and believe the right things. So a child who says yes to Jesus is going to be celebrated because they have done what is expected of them. But for those who might be LGBTQ+ identifying, it might be a rule of adhering to straightness. A lot of my interviewees essentially denied their sexuality or their gender because of the rules of camp. There also might be accepted norms of whiteness. So for me, camp was the place of the deepest sense of belonging I ever experienced. Part of why I belonged, though, was because I fit the mold. I said the right things, I was extroverted, and that part of my personality fit what camp was looking for. Camp can be an incredible place of belonging, and it can also be a place of deep exclusion.

What is “cry night,” and why did it leave such a lasting impact on so many of the folks you interviewed?

Every single person I interviewed shared some experience around it. During the camp experience within white evangelical environments, there is often a night in which campers are encouraged to get right with God. And that, again, is part of that trajectory of conversion. Because donors need to see tangible results of their dollars, camp directors might be standing in the back taking notes of how many kids accepted Jesus into their heart. So you have this night at camp of heightened emotions, and oftentimes on that night, the message of Jesus on the cross is given.

It’s typically also presented through the atonement theory of penal substitution. As one interviewee noted, that theory is used ubiquitously because it’s the one that gets results. Oftentimes, the way that message is received by children and youth is as a message of them having killed Jesus, of them having put Jesus on the cross. And from that there are extremely heightened emotions, and they might feel bad, they might want to get right with God. There might be guilt or shame involved.

If not conversion, what should be the main point of evangelical church camps?

I do not find a home under white evangelicalism anymore — I find a home in the Episcopal tradition, and so there are certainly differences in belief systems. But I do still believe camps are holy, sacred places. And I believe they are places where God is still present and where God will meet humans. I think if we could rid camps of the need of conversion, that would be enough. What if it was just simply kids being out in nature with other grownups who love them, where creation and creator can meet, where God could just show up on God’s own time?

If I were to speak as a camp speaker now in one of those environments, I think the message I would give over and over again would simply be a message of love. God loves you for exactly who you are, as you are. God is love, and who you are as a young person is exactly who God celebrates.

You write that church camp has housed your greatest joy and greatest grief. Can you explain that more?

Camp is a hilarious place. It is big, bright and robust, it is campy. And I hold that alongside the harm that oftentimes happens in these environments — both the theological harm, if it happens, but also the harm that happens toward particular groups. So for me, that tension is very real. And I would say it’s very real for so many people who are leaving white evangelicalism, who are experiencing deconstruction or spiritual evolution, who are feeling a little wayward in their faith right now with everything going on in our country. I think a lot of folks are at this place of tension when it comes to their memories, but also who they are now.

Two of the book events I’ve hosted ended up being less bookish and more places of permission for people to begin processing their own spiritual trauma — many of whom experienced trauma not even necessarily within a camp environment but within white evangelical spaces as a whole. There is so much grief that people are holding in. These spaces were just their everything until they weren’t.