(RNS) — There will be no government-established religious charter school in Oklahoma. With Amy Coney Barrett having recused herself for unexplained but surmisable reasons, the remaining Supreme Court justices on Thursday split 4-4 on the question, thereby letting stand the Oklahoma Supreme Court’s thumbs-down on the school.

Since SCOTUS did nothing more than announce the split, there’s no record of who voted how, much less why they did. That is surmisable, too, but let’s first review the bidding.

Two years ago, the Oklahoma charter school board approved an application from the Catholic Archdiocese of Oklahoma City and the Diocese of Tulsa to create an explicitly religious virtual charter school, St. Isidore of Seville, which would participate in “the evangelizing mission of the church.” This was challenged in court by the state attorney general, who considered the arrangement a violation of both the U.S. Constitution’s establishment clause and the state’s constitutional ban on the direct or indirect use of public money “for the use, benefit, or support of any sect, church, denomination, or system of religion, or for the use, benefit, or support of any priest, preacher, minister, or other religious teacher or dignitary, or sectarian institution as such.”

That ban, which went into effect when Oklahoma became a state in 1907, was upheld by voters in a 2016 referendum. But the current state educational establishment, led by State Superintendent of Public Instruction Ryan Walters, is hell-bent on sluicing as much religion as possible into public education.

Thus, after the Oklahoma Supreme Court decided in favor of the attorney general, the charter school board took the case up to the U.S. Supreme Court. Barrett likely recused herself because she is close friends with a law professor who was an adviser to St. Isidore’s as well as a faculty fellow at Notre Dame’s Religious Liberty Clinic, which represented the school.

At oral argument April 30, the central legal question for the court had to do with whether St. Isidore’s was for all intents and purposes a public school and thus barred from receiving public funds because of its religious mission. Unsurprisingly, the three liberal justices made clear that they saw it this way. So far as they were concerned, the issue came down to the need to prevent the use of public funds for explicitly religious purposes.

The consensus of court watchers is that the fourth vote on their side came from Chief Justice Roberts, who seemed troubled by the setup in a way the other conservative members of the court weren’t. Comparing the role of the government in recent decisions requiring religious organizations to be treated the same as secular ones, Roberts said, “This does strike me as a — a much more comprehensive involvement.”

Underlying the case is the extent to which the establishment clause forbids public endorsement of, and support for, religion.

Those on the religious right have long claimed that the framers of the Constitution merely intended the establishment clause to prevent the federal government from creating something like the Church of England for the United States. As evangelical pseudo-historian David Barton put it in his book “Original Intent”: “The constitutional prohibition against “an establishment of religion” forbade only the federal establishment of a national denomination.”

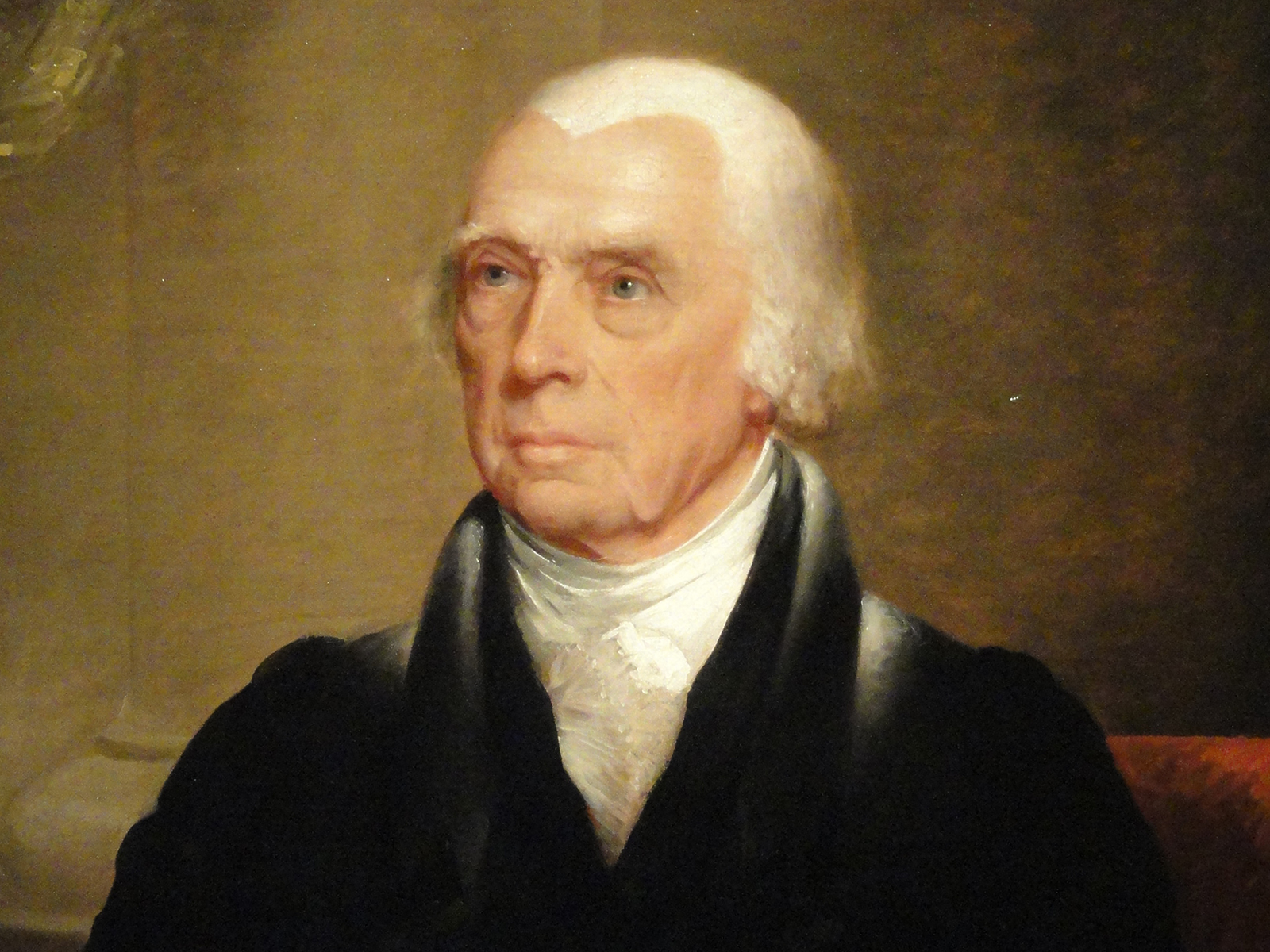

But that’s not how James Madison, who chaired the congressional conference committee that devised the language of the clause (which was contained in neither the House nor Senate versions of the Bill of Rights), saw it.

In 1811, when Madison was president, Congress passed a bill to incorporate the Episcopal Church in Alexandria, which was then part of the District of Columbia and thus under federal jurisdiction. Madison vetoed the bill as violating the First Amendment’s edict that “Congress make no law respecting an establishment of religion” on a number of grounds, including:

Because the bill vests in the said incorporated church an authority to provide for the support of the poor and the education of poor children of the same, an authority which, being altogether superfluous if the provision is to be the result of pious charity, would be a precedent for giving to religious societies as such a legal agency in carrying into effect a public and civil duty.

Not only did the bill have nothing to do with creating a national denomination, but in Madison’s view it violated the establishment clause by giving a religious institution a public job to do — and his veto carried the day. On reconsideration, the House of Representatives sustained it by a vote of 74 to 29.

It is clear that Madison understood “no law respecting an establishment of religion” as disallowing any legal authorization (such as incorporation) of a religious body. This very strict separationist understanding of the establishment clause is, to be sure, a far cry from how the clause has been interpreted by the modern Supreme Court even at its most separationist. A longstanding example is its acceptance of government funding of religious institutions to undertake social service provision.

It is likely that another case involving a religious charter school will in due course make its way to the Supreme Court and that this will not be one where Barrett feels compelled to recuse herself. That, however, is no guarantee of a win for the school. Barrett has shown herself interested, apparently like Roberts, in finding some basis for maintaining establishment clause limits on public funding of religion.

In the meantime, those who claim to be committed to following the original intent of the framers might ponder what Madison as well as the voters of Oklahoma had to say.