(The Conversation) — Every few years, a story about Columbus resurfaces: Was the Genoese navigator who claimed the Americas for Spain secretly Jewish, from a Spanish family fleeing the Inquisition?

This tale became widespread around the late 19th century, when large numbers of Jews came from Russia and Eastern Europe to the United States. For these immigrants, 1492 held double significance: the year of Jews’ expulsion from Spain, as well as Columbus’ voyage of discovery. At a time when many Americans viewed the explorer as a hero, the idea that he might have been one of their own offered Jewish immigrants a link to the beginnings of their new country and the American story of freedom from Old World tyranny.

The problem with the Columbus-was-a-Jew theory isn’t just that it’s based on flimsy evidence. It also distracts from the far more complex and true story of Spanish Jews in the Americas.

In the 15th century, the kingdom’s Jews faced a wrenching choice: convert to Christianity or leave the land their families had called home for generations. Portugal’s Jews faced similar persecution. Whether they sought a new place to settle or stayed and hoped to be accepted as members of Christian society, both groups were searching for belonging.

Jewish religious items at the Museo Metropolitano in Monterrey, Mexico.

Thelmadatter/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

We are scholars of Jewish history and have been working on the first English translations of two texts from the 16th century. “The Book of New India,” by Joseph Ha-Kohen, and the spiritual writings of Luis de Carvajal are two of the earliest Jewish texts about the Americas.

The story of the New World is not complete without the voices of Jewish communities that engaged with it from the very beginning.

Double consciousness

The first Jews in the Americas were, in fact, not Jews but “conversos,” meaning “converts,” and their descendants.

After a millennium of relatively peaceful and prosperous life on Iberian soil, the Jews of Spain were attacked by a wave of mob violence in the summer of 1391. Afterward, thousands of Jews were forcibly converted.

Synagogue of El Tránsito, a 14th-century Jewish congregation in Toledo, Spain.

Selbymay/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

While conversos were officially members of the Catholic Church, neighbors looked at them with suspicion. Some of these converts were “crypto-Jews,” who secretly held on to their ancestral faith. Spanish authorities formed the Inquisition to root out anyone the church considered heretics, especially people who had converted from Judaism and Islam.

In 1492, after conquering the last Muslim stronghold in Spain, monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella gave the remaining Spanish Jews the choice of conversion or exile. Eventually, people who converted from Islam would be expelled as well.

Among Jews who converted, some sought new lives within the rapidly expanding Spanish empire. As the historian Jonathan Israel wrote, Jews and conversos were both “agents and victims of empire.” Their familiarity with Iberian language and culture, combined with the dispersion of their community, positioned them to participate in the new global economy: trade in sugar, textiles, spices – and the trade in human lives, Atlantic slavery.

Yet conversos were also far more vulnerable than their compatriots: They could lose it all, even end up burned alive at the stake, because of their beliefs. This double consciousness – being part of the culture, yet apart from it – is what makes conversos vital to understanding the complexities of colonial Latin America.

By the 17th century, once the Dutch and the English conquered parts of the Americas, Jews would be able to live there. Often, these were families whose ancestors had been expelled from the Iberian peninsula. In the first Spanish and Portuguese colonies, however, Jews were not allowed to openly practice their faith.

Secret spirituality

One of these conversos was Luis de Carvajal. His uncle, the similarly named Luis de Carvajal y de la Cueva, was a merchant, slave trader and conquistador. As a reward for his exploits he was named governor of the New Kingdom of León, in the northeast of modern-day Mexico. In 1579 he brought over a large group of relatives to help him settle and administer the rugged territory, which was made up of swamps, deserts and silver mines.

A statue in Monterrey, Mexico, of Luis Carvajal y de la Cueva.

Ricardo DelaG/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

The uncle was a devout Catholic who attempted to shed his converso past, integrating himself into the landed gentry of Spain’s New World empire. Luis the younger, however, his potential heir, was a passionate crypto-Jew who spent his free time composing prayers to the God of Israel and secretly following the commandments of the Torah.

When Luis and his family were arrested by the Inquisition in 1595, his book of spiritual writings was discovered and used as evidence of his secret Jewish life. Luis, his mother and sister were burned at the stake, but the small, leather-bound diary survived.

A 19th-century depiction of the execution of Luis de Carvajal the Younger’s sister.

‘El Libro Rojo, 1520-1867’ via Wikimedia Commons

Luis’ religious thought drew on a wide range of early modern Spanish culture. He used a Latin Bible and drew inspiration from the inwardly focused spirituality of Catholic thinkers such as Fray Luis de Granada, a Dominican theologian. He met with the hermit and mystic Gregorio López. He discovered passages from Maimonides and other rabbis quoted in the works of Catholic theologians whom he read at the famed monastery of Santiago de Tlatelolco, in Mexico City, where he worked as an assistant to the rector.

His spiritual writings are deeply American: The wide deserts and furious hurricanes of Mexico were the setting of his spiritual awakenings, and his encounters with the people and cultures of the emerging Atlantic world shaped his religious vision. This little book is a unique example of the brilliant, creative culture that developed in the crossing from Old World to New, born out of the exchange and conflict between diverse cultures, languages and faiths.

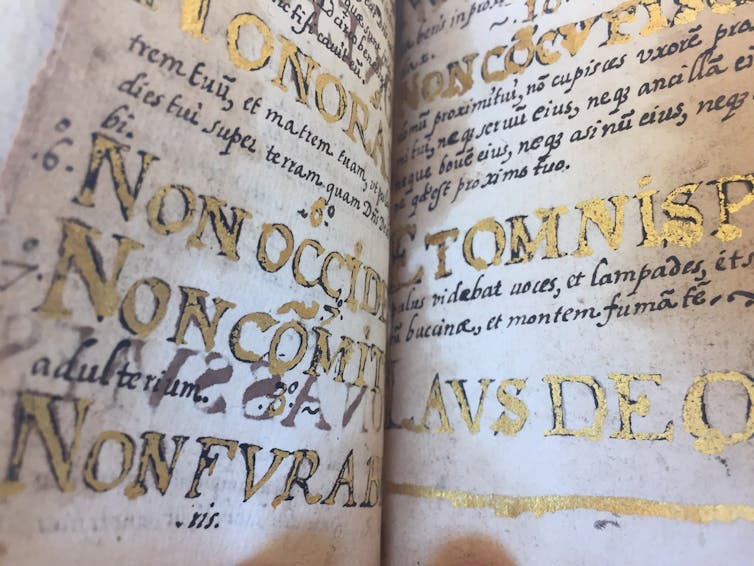

A glimpse of Luis de Carvajal’s spiritual writings, photographed in New York City.

Ronnie Perelis

More than translation

Spanish Jews who refused to convert in 1492, meanwhile, had been forced into exile and barred from the kingdom’s colonies.

The journey of Joseph Ha-Kohen’s family illustrates the hardships. After the expulsion, his parents moved to Avignon, the papal city in southern France, where Joseph was born in 1496. From there, they made their way to Genoa, the Italian merchant city, hoping to establish themselves. But it was not to be. The family was repeatedly expelled, permitted to return, and then expelled again.

Despite these upheavals, Ha-Kohen became a doctor and a merchant, a leader in the Jewish community – earning the respect of the Christian community, too. Toward the end of his life, he settled in a small mountain town beyond the city’s borders and turned to writing.

After a book on wars between Christianity and Islam, and another one on the history of the Jews, he began a new project. Ha-Kohen adapted “Historia General de las Indias,” an account of the Americas’ colonization by Spanish historian Francisco López de Gómara, reshaping the text for a Jewish audience.

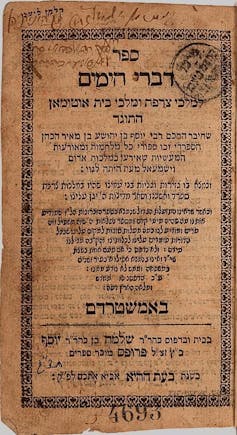

A 1733 edition of ‘Divrei Ha-Yamim,’ Ha-Kohen’s book about wars between Christian and Muslim cultures.

John Carter Brown Library via Wikimedia Commons

Ha-Kohen’s work was the first Hebrew-language book about the Americas. The text was hundreds of pages long – and he copied his entire manuscript nine times by hand. He had never seen the Americas, but his own life of repeated uprooting may have led him to wonder whether Jews would one day seek refuge there.

Ha-Kohen wanted his readers to have access to the text’s geographical, botanical and anthropological information, but not to Spain’s triumphalist narrative. So he created an adapted, hybrid translation. The differences between versions reveal the complexities of being a European Jew in the age of exploration.

Ha-Kohen omitted references to the Americas as Spanish territory and criticized the conquistadors for their brutality toward Indigenous peoples. At times, he compared Native Americans with the ancient Israelites of the Bible, feeling a kinship with them as fellow victims of oppression. Yet at other moments he expressed estrangement and even revulsion at Indigenous customs and described their religious practices as “darkness.”

Translating these men’s writing is not just a matter of bringing a text from one language into another. It is also a deep reflection on the complex position of Jews and conversos in those years. Their unique vantage point offers a window into the intertwined histories of Europe, the Americas and the in-betweenness that marked the Jewish experience in the early modern world.

(Flora Cassen, Senior Faculty, Hartman Institute and Associate Professor of History and Jewish Studies, Washington University in St. Louis. Ronnie Perelis, Associate Professor of Sephardic Studies, Yeshiva University. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)