(RNS) — Since childhood, I’ve been a regular target of ignorance and bigotry. My experience contributed to my becoming a scholar of history and religion, but more than that, it has given me a clearer view of how identity can fuel belonging or isolation. Now that I’m a father to two young girls, disrupting bias and encouraging empathy feels urgent and necessary, a personal and professional responsibility.

In a world that feels more polarized by the day, how do we disrupt bias and encourage connection?

Empathy doesn’t just appear on its own. In large part, it has to be nurtured, and ages 1 to 6 is a prime window. While temperament plays a role, so does a child’s environment, including the people and stories they’re exposed to.

There aren’t many children’s books centered on Sikh characters or on Sikh American life, so I decided to write some myself — a move that made at least one scholarly colleague raise an eyebrow. A grand plan? Yes. But it’s my belief, my hope, my conviction that picture books can change the world.

Signs of empathy appear in the first year or two of life, when infants may cry in response to another person’s distress. By age 3, this emotional responsiveness is joined by cognitive empathy, or the ability to accurately imagine another person’s experience. The ability to “feel” for another person likely comes from specific brain cells that automatically and unconsciously mirror others’ emotions as our own.

Evidence of empathy in young kids — spontaneous helping or sharing — is correlated with prosocial behaviors in adulthood. Establishing these empathetic pathways early in life matters; it can be hard to make up ground if you miss the window.

Practicing empathy is wholly dependent on being exposed to other people’s feelings. This happens through socialization — with parents, siblings, friends, and also through stories. A groundbreaking 2006 study in the Journal of Research in Personality found that the tendency to become absorbed in a story was associated with greater empathy and social ability. Another study demonstrated that fiction, especially narratives that transport readers out of their own world, influences readers’ capacity for understanding.

Picture books, specifically, help little kids navigate their big emotions while at the same time fostering an ability to see the world through someone else’s eyes. I distinctly remember experiencing this as a child when I read “The Snowy Day,” a book about a Black boy very different from me, living everyday life and finding joy.

If stories help kids develop empathy and connect with others, then the questions become: Whose stories are my kids — are all American kids — exposed to? Whose feelings and experiences do they have a chance to connect with, and what values are they learning from them?

In recent years, children’s literature has become increasingly diverse, involving a multiplicity of voices and perspectives. Our kids now have more points of connection. The Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison reports that in 2024, 51% of almost 3,500 children’s and young adult books featured significant content related to people of color. Thirteen percent featured Asian characters.

These proportions reflect the U.S. population fairly well, which is a good indication of the progress we’ve made over the past few decades. Still, raising your kids as part of a minority, especially one that faces misrepresentation in the media, can feel isolating.

I began writing children’s books as a way to share my Sikh traditions so they could be seen and accepted for what they are. I’ve long felt that storybooks engage in more complex concepts and emotions than books for older kids: They’re capacious and visual enough to explore big, wild ideas, yet narrow enough to be digestible and pragmatic. I took inspiration from so many children’s book authors, especially Vashti Harrison, the author-illustrator behind the books “Hair Love,” “Big” and others.

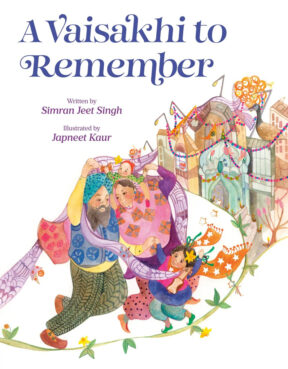

“A Vaisakhi to Remember” by Simran Jeet Singh. (Courtesy image)

Storybooks expand representation by honoring the cultural and subjective nuances of identity, helping us see both ourselves and one another more clearly. My first picture book, “Fauja Singh Keeps Going,” tells the true story of the oldest person to ever run a marathon, a tale that challenged my assumptions about what a hero could look like: living with disability, elderly, unable to read, an immigrant.

My latest, “A Vaisakhi to Remember,” centers on a harvest holiday among Punjabi farmers that has evolved into the most significant celebration in the Sikh tradition. It traces the migration of a girl from her village in Punjab to a city in North America. Her search for belonging is at once personal and universal: It’s uncomfortable to change schools, or to move to a new house, or to immigrate. I intentionally left Punjabi phrases and terms untranslated, a wink to my Sikh and Punjabi readers, an “I see you” that can mean so much for people who live on the margins of society and often feel invisible.

But picture books, even ones about Sikh children, aren’t only to provide a sense of belonging. When Sesame Workshop compiled its 2024 State of Well-Being Report, 84% of Americans and 93% of educators said that having more kindness-focused characters in children’s media is important in helping kids be more kind. As a children’s book author, I also want to create a point of connection that serves as the first step toward compassion.

Picture books help kids learn that difference isn’t scary or even all that unusual. It’s an utterly human fact that they will encounter every day. What if, instead of being fearful, children could embrace differences with the openness and curiosity that seems to come so naturally to them?

When kids are given the opportunity to practice feeling for others early and often, it can help build the more compassionate world I hope my children — all of our children — will inherit.